Gregory Charles Rivers is arguably the most famous gweilo in Hong Kong.

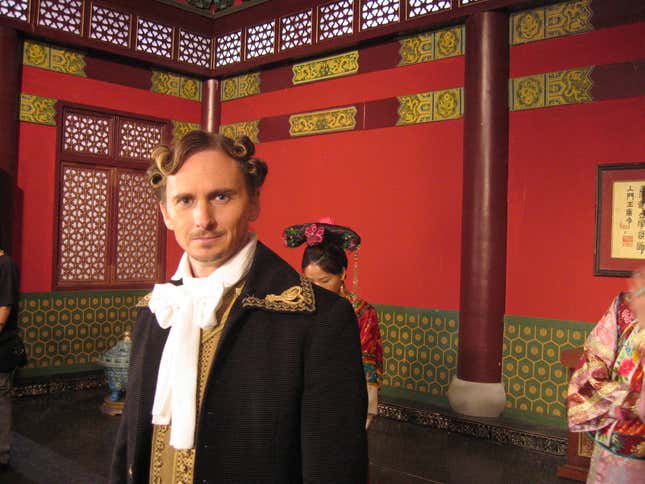

His name might not ring a bell in his native Australia, but Rivers’s face is instantly recognizable for people who’ve grown up watching TVB, Hong Kong’s largest broadcaster and a mainstay of Chinese homes around the world. Over his prolific 20-year acting career, he’s appeared in more than 200 soap operas in typical white-guy parts like high-ranking police officers and foreign ambassadors in dynastic China.

His fluent Cantonese and love for Hong Kong has earned him great popularity among local young people fighting to safeguard their cultural identity amid mainland China’s growing influence on the city’s affairs.

But none of this was part of Rivers’s plans when he bought a one-way ticket to Hong Kong from Australia in 1987. What he wanted to do was follow in the footsteps of his heroes: Cantopop stars Alan Tam and Leslie Cheung. Now, three decades later, the 53-year-old will finally get that opportunity with his debut concert taking place in Hong Kong on May 31 and June 1.

“If I don’t do this now, this might never happen in my whole life,” Rivers told Quartz in an interview conducted in Cantonese. “I just want to tell people that if you work hard, your dream will eventually come true.”

The Cantopop dream

Born in Gympie, Queensland, Rivers was studying medicine at the University of New South Wales when he heard a new genre of music played by his Hong Kong classmates in their dormitory.

The catchy melodies by the likes of Alan Tam and Leslie Cheung were sung in a language he did not understand. “I cannot explain why I loved it so much,” he recalls. “I bought the vinyl records and learned the Chinese lyrics while my other Australian friends were into heavy metal.”

Then by chance, he landed a gig in Sydney to be Tam’s driver during a show in 1986. His love for Cantopop was recognized by Tam’s people, and he was invited to sing on stage with him.

That tantalizing taste of Cantopop stardom led him to move to Hong Kong a year later, adopting the Chinese name Ho Kwok-wing: Ho (河) is the Chinese character for river, and Kwok-wing (國榮) is an homage to the late superstar Leslie Cheung, who had the same given Chinese name. As it would turn out, Rivers did find stardom, just not in music, though he continued singing in small showcases.

He thought of giving up on his music ambitions, but in 2016, he was asked to perform at a music-awards show organized by local satirical magazine 100Most. He performed two songs, including the rap song “True Hong Kong Land” (video above), and was presented the best Hong Kong male singer at the gala. “It gave me hope again,” he said.

His Cantonese singing is also popular in the mainland. Last year, he was invited to perform on Shanghai’s Dragon Television. Of more than 70 foreigners singing Chinese pop songs, he was among two who performed in Cantonese. The Chinese show hosts were impressed with both his Cantonese singing and conversational Mandarin. A video of his performance (below) was viewed more than 2 million times on the mainland.

Cantonese’s unlikely advocate

Rivers has prepared 40 songs for his two-night show titled Dare to Dream—a mix of mostly Cantopop with a few Mandarin titles. The songs he’s chosen are supposed to reflect his own Cantopop journey, and include two of his early favorites: “The Root of Love” and “Will Never Think About You” by Alan Tam. One of the most challenging songs Rivers will sing is Eason Chan’s “Under Mount Fuji,” which he spent months practicing because he said it could come off as robotic if not performed correctly.

Getting ready for the concert means overseeing many other details, such as the concert art. Under his creative direction, he decided for one photograph to pose as if he were singing but into a skewer of curry fish balls, an iconic Hong Kong street food, instead of a microphone.

After one of these planning meetings, he and his wife, Bonnie Cheung, decided to go to a cafe in Kowloon and ended up in a heated discussion. But it wasn’t concert arrangements they were talking about. Rivers was giving his point of view about a contentious paper from Hong Kong’s education bureau (link in Chinese).

The paper, written in 2013 by Chinese scholar Song Xinqiao, caused public outcry this month when it resurfaced online. The report, which states that Cantonese is merely a dialect, not a mother tongue, quickly became the talk of the town.

“Cantonese is, of course, Hong Kong’s mother tongue. How can you argue about that?” said Rivers. These days, Rivers admits he speaks Cantonese more than English and is prone to weaving Hong Kong slang into his text messages, which are composed, of course, in Chinese.

Cantonese, the lingua franca of Hong Kong, remains a source of tension between Hong Kong and the mainland. Since Hong Kong’s handover to China in 1997, the Hong Kong government has made moves to diminish the influence of Cantonese. In 2014, Hong Kong’s education bureau had claimed in an article on its website that Cantonese was not an official language, but the piece was swiftly removed amid public discontent. Benjamin Au Yeung, an expert in Cantonese and former senior lecturer at Chinese University in Hong Kong, has accused the government (video in Cantonese) of intentionally suppressing the teaching of Cantonese to gain Beijing’s favor.

In a town brimming with expats, Rivers’s views on Cantonese is one of the reasons locals see him as one of their own. In a 2016 interview, his fierce defense of Hong Kong culture (video in Cantonese) and concern that Cantonese could one day vanish earned him wide regard as a “genuine Hongkonger.” In a way, one can see his upcoming concert as both a dream 30 years in the making and a love letter to his adopted home and language.