Ultra-cold freezers are suddenly a hot commodity.

One of the most advanced US coronavirus vaccines, created by Pfizer in partnership with BioNTech, has to be stored at -70° Celsius (-94° Fahrenheit), or around 30°C colder than the North Pole in winter. It’s not certain that the vaccine will be approved for widespread distribution. But, if it is, very few freezers go that cold.

“There’s no precedent for vaccines to be stored at that low of a temperature,” says Soumi Saha, a pharmacist and director of advocacy at Premier, which arranges healthcare purchases for hospitals, nursing homes, and other providers. Most vaccines are transported along the cold chain network at 2° to 8°C (35° to 46°F), with the odd vaccine requiring temperatures as low as -25°C (-13°F.)

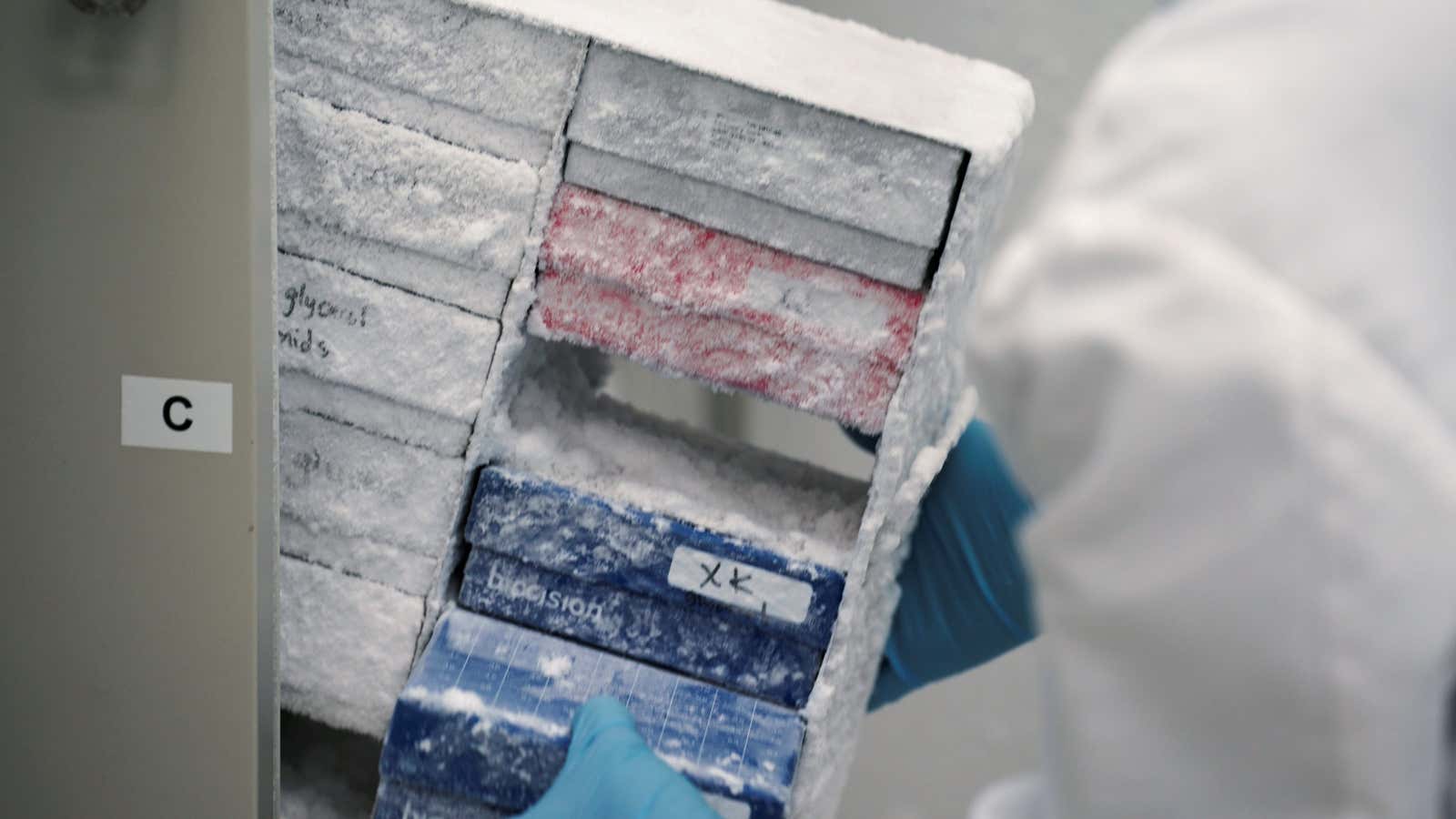

Those few US freezers that can reach -70°C are typically lab freezers, says Saha, which have completely different regulatory requirements from pharmaceutical freezers.

As a result, “states are surveying their networks to understand where sub 80 freezers are,” says Julie Swann, head of the department of industrial and systems engineering at North Carolina State University, who advised the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

North Carolina, for example, is home to a major biotech industry, and so it could have more ultra-cold freezers than elsewhere; Swann estimates there could be 10 locations across the state with such cold storage. But other states will have fewer options. “This will be very different in New York or Massachusetts than Kansas or Wyoming,” she says. “A lot of this will be driven by density and industry.”

The CDC has explicitly told states not to invest in ultra-cold freezers just yet; too much is still unknown about what vaccine will be available and how it will be transported. “If I were the state, I’d still buy one,” says Swann. “I might not buy 20, but I’d buy a few.” Swann said she checked with a few cold storage companies, none of which had suitable freezers.

Freezers aren’t the only complicated part of distribution for the Pfizer vaccine. “The complexities of this plan for vaccine storage and handling will have major impact in our ability to efficiently deliver the vaccine,” Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said at a CDC panel in August.

Pfizer has created containers that will keep about 1,000 to 5,000 doses at -75°C (plus or minus 15°) for 10 days, kept cold with dry ice. The company is also partnering with UPS to build two freezer farms, one in Louisville, Kentucky and the other in the Netherlands, that can house 48,000 vials of vaccine at -80°C (-112°F.)

Once the vaccines have thawed, they can be kept in the fridge for five days—but this time can be quickly eaten up in the commute. “If the product’s only good for 10 days and it takes two or three to get to a rural community, you’ve already lost 30% of the time frame that product is viable,” says Saha.

This set-up will create considerable pressure to send out hundreds of vaccines every day. “The transport costs would be extremely high,” says Prashant Yadav, a healthcare supply chains expert at Harvard Medical School.

Pfizer isn’t worried. “This is what we do every day. We have years of proven experience in supply chain and cold chain management,” said a spokesperson.

But a final distribution plan would inevitably be constrained by the locations of medical deep freezers. Sending out thousands of vaccines at a time works for mass vaccination clinics, says Swann, where people are encouraged to travel to the vaccination site to receive their dose. “It doesn’t help you give out a few doses here or there. That’s much more difficult,” she says. The Pfizer vaccine’s requirements makes it much harder to deliver to rural areas, where there may not be 1,000 people who are able to receive the vaccine within the short window available. “That’s where we’re concerned about waste,” says Saha.

Delivering shots at mass vaccination clinics also makes it harder to prioritize giving the vaccine to select groups. Plenty of care homes have hundreds, rather than thousands of patients. “It’s possible you’ve now wasted that vaccine if you weren’t able to use it on other priority patients,” says Swann. Pfizer says it’s working on smaller containers that will be ready by 2021.

Another vaccine in advanced trials, created by Moderna, requires shipping at -20°C, which is also colder than most vaccines. But there are more storage facilities capable of reaching that temperature than at -70°C. Some experts believe distribution will be more seamless if it follows the cold route distribution system laid out during H1N1. “In some sense we’ve had our test pandemic,” says Swann. “Any time you can re-use your learnings from a test case, or trial run, that’s better than having to create systems from scratch or change the systems.”

If trials continue to go well, there’s hope that multiple coronavirus vaccines will be available. In such a scenario, the Pfizer vaccine could potentially be used for mass vaccination clinics, while other vaccines would be used for more specialized or remote areas. This all depends on the effectiveness of the shots in the pipeline. If Pfizer’s produces the best results, there will be pressure to distribute it as widely as possible, even if the cold chain freezes over.