- The coronavirus pandemic has ignited fears of a global recession.

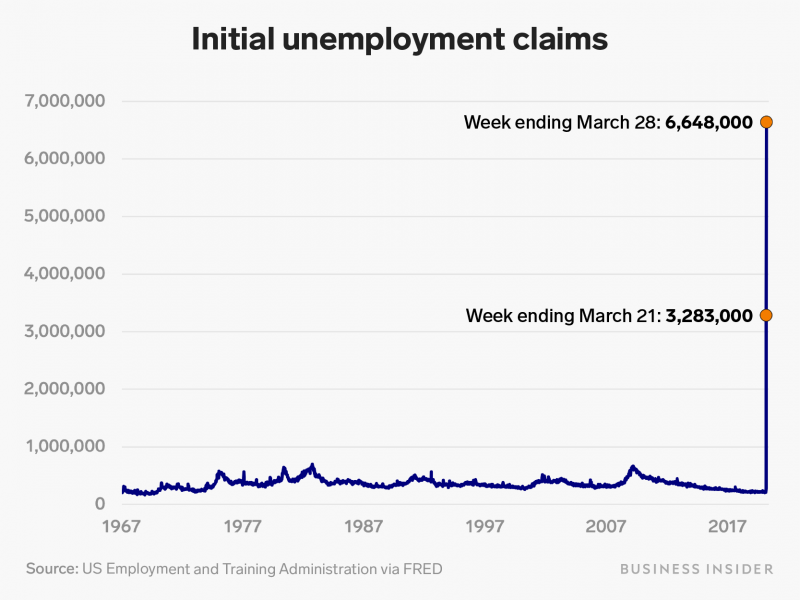

- In the week ending March 28, a record 6.6 million people in America filed for unemployment.

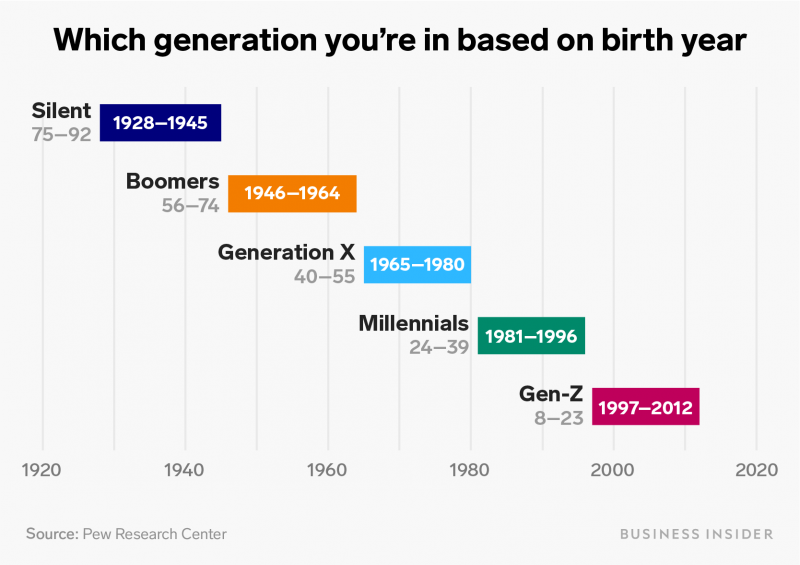

- A recession would spell particularly bad news for millennials, who will turn 24 to 39 this year, since the oldest among them weathered the Great Recession early in their careers, if not immediately after college.

- Millennials have been dealing with a nationwide affordability crisis since the Great Recession ended, balancing increasing living costs and massive student-loan debt with stagnating wages.

- Business Insider talked with dozens of experts and millennials to see how a second recession would affect a generation that’s still financially behind from the last one.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Greg Anderson is no stranger to long days.

For months, the 34-year-old furniture salesman has been getting up at 6 a.m. and working until 9 p.m. He spends 12 hours on the floor, six days a week, at the Raymour & Flanigan in Reading, Pennsylvania, selling furniture and talking to clients.

The schedule might look crushing, but after spending nearly a year job-hunting and three months not looking for work at all, Anderson is logging the extra hours for extra money. And while he enjoys seeing the hours pay off, it’s not the life he used to envision.

In 2007, Anderson was a Korean-fusion chef at a restaurant in Los Angeles, where he lived in a $750-a-month apartment. Feeling burned out, he took a break and left for Southeast Asia. The day he boarded the plane just so happened to be September 16, 2008, the day after the investment bank Lehman Brothers collapsed, setting off the cascade of stock-market crashes and investment-bank failures that kick-started the global financial crisis of 2008.

"I came back to a completely different world," Anderson told Business Insider of his return to the US six months later. Business at his former restaurant was declining, leaving him out in the cold when he inquired for work again.

After spending a month apartment-hunting in LA, Anderson went to Reading and moved in with his mom, who helped get him a job as an office manager. Since then, Anderson has worn many titles, among them optician, writer, and full-time student at a community college.

"I realized I could never return to the chef's world," he said, adding that if it weren't for the Great Recession, he'd "probably still be in LA in cooking."

"It was a passion until I stepped away from it," he said. "The only job I could get in food at Reading was McDonald's at $8 an hour. It kind of ruined it for me."

More than a decade later, Anderson and many of his American millennial peers are still dealing with the aftermath of the last recession - at a time when they're also facing the high possibility of another one. Multiple Wall Street firms have predicted that the US will fall into a recession from the social-distancing measures brought on by the coronavirus pandemic, while some experts have said that the country, and the world, is already in one.

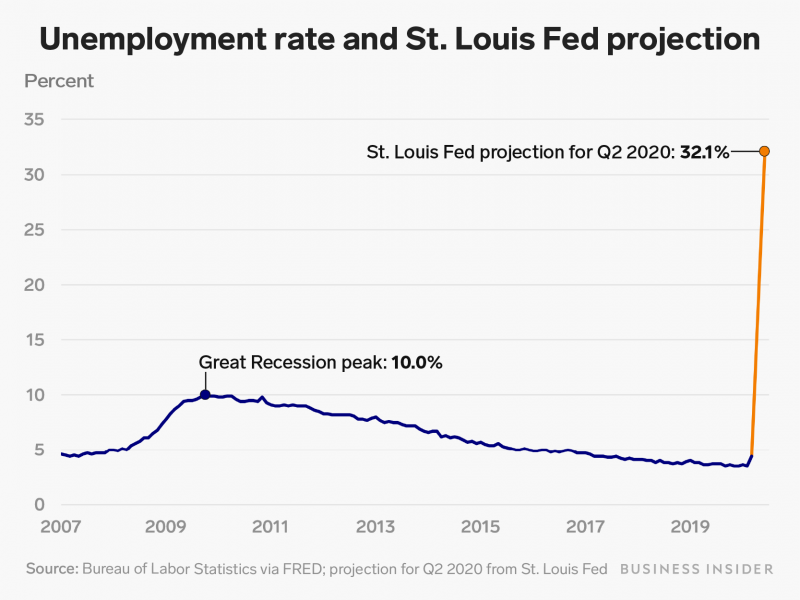

As the coronavirus swept across the US, the Dow saw its biggest drop since 1987. It has since rebounded, but the stock market has been teetering between a bear market and a bull market for four weeks. And as businesses from retailers to restaurants have been forced to temporarily close their doors, unemployment claims have hit a record high of 6.6 million for the week ended March 28. That broke the record of 3.3 million claims set just the week before, for the seven days ended March 21.

To find out how the last financial crisis affected millennials, I spoke with dozens of people between the ages of 24 and 39 across the US who shared stories of their struggles finding work and building long-term wealth. I also spoke with nearly a dozen experts - economists, generational researchers, and financial advisers - who explained the devastating effects a recession can have on each generation and why the last one was so brutal in particular for America's youngest generation at the time.

As Anderson's situation shows, millennials haven't yet been able to put the Great Recession in the past. How will a generation still playing catch-up from the 2008 financial crisis face up to a second recession before its oldest members even turn 40?

Millennials still feel the lingering gravity of the last financial crisis

The financial crisis of 2008 left no generation untouched: Silent, boomer, and Gen X households all experienced wealth loss. The younger the generation, the worse the short-term repercussions; Gen X (those born between 1965 and 1979) was hit hardest, wealthwise, but it also recovered best.

In 2018, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis' Center for Household Financial Stability took a deep dive into the demographics of wealth, analyzing more than 25 years' worth of Fed data. One of the series' reports sought to find out to what extent the recession had altered American families' financial behaviors. Two of the report's authors, Bill Emmons, assistant vice president and lead economist at the St. Louis Fed, and Lowell Ricketts, lead analyst, spoke with me about the generational effects of recessions, expressing individual views that aren't on behalf of the Fed.

They found that the 2008 economy served an especially potent cocktail of income loss and wealth decline to the 30- and 40-somethings - many of whom were recent homeowners - in the form of unemployment and the housing downturn. Even though the older families past age 50 also lost wealth, Emmons said, they were more insulated from the job market and managed to recover.

But when it comes to millennials, defined by Pew as those who will turn 24 to 39 in 2020, the story takes on a different tone.

Mark Muro, a senior fellow and policy director at the Brookings Institution, told me that millennials were colored by the catastrophe of the last financial crisis. "Millennials have lifelong damage, given the severity of the Great Recession," he said. "They're still overshadowed by it, with new consequential burdens coming at them."

When the crisis began in 2007, the oldest millennials were 26, an age at which most of the generation hadn't yet accumulated substantial wealth. It's this cohort that bore the true brunt of the financial crisis. From the very beginning of their careers, they entered a tough job market and experienced wage stagnation. On top of that, they faced rising living costs and were confronted with their own student-loan debt, which, thanks to low wages, was difficult to repay.

According to the St. Louis Fed's report, millennials born in the 1980s are at risk of becoming a "lost generation" that may never be as rich as their parents. As of 2016, people born in the '80s had 34% less wealth than they likely would have if the financial crisis hadn't occurred, the report found.

As Muro put it, "older millennials were squarely hammered."

Older millennials were squarely hammered.

Twelve years later, the financial situation still looks bleak for millennials, who have found themselves in an affordability crisis. As of 2017, young adults ages 25 to 34 had seen only a $29 increase in their income compared with their counterparts in 1974 when adjusted for inflation, while those ages 45 to 54 saw income growth of $5,400 over the same period. Millennials' paltry wage increase hasn't kept up with all the living costs that inflated in the 2010s, including rent, home prices, and college tuition.

Another recession could be a double whammy for older millennials - especially homeowners with mortgages

Dan Ceresia, a 38-year-old single dad of two who lives in Napa, California, graduated from college in 2009, right after the Great Recession.

Unable to find work with his degrees in mass communications and theater, he spent years cycling through various jobs: insurance agent at Geico, lab technician at LensCrafters, wine buyer at Bread Garden Market. The latter led him to complete an executive MBA from Sonoma State University's Wine Business Institute, and he has spent the past 2 1/2 years looking for work and picking up side gigs. In late 2019, a decade after graduating, he finally launched his own wine-consultancy business.

It's the oldest millennials - people like Ceresia and Anderson - who are of the gravest concern to Muro. They're hitting life milestones like starting a family and buying a home, but they don't have the same time that younger generations do to get back on track financially. Many haven't yet paid off student loans and can't afford to buy a home, leaving them in the spiral of renting. And of the 28% who have bought homes and have a mortgage, half owe more than $100,000, a 2019 survey by Insider and Morning Consult found.

The result, Muro said, is a recipe that could yield "disturbing impacts" in a second recession.

While Emmons said he wasn't expecting another housing disaster - and Ricketts added that they were seeing more stable endings in the mortgage market - it would spell bad news for the millennials who recently bought houses and have a lot of debt.

The Insider and Morning Consult survey also found that half of the millennial respondents had delayed buying a home because of money. Hiding behind that statistic is the glimmer of a financial positive: Because younger generations are waiting longer to become homeowners, families might not have to borrow as much by the time they buy, and lower prices might be helpful in an entry-level market, Emmons and Ricketts said. Those who haven't purchased, like Ceresia, won't be hurt by a decline in an asset they don't have.

But some have resigned themselves to the reality that they'll never be able to buy. Ceresia said the Great Recession prevented him from accumulating assets and developing the level of wealth for such a purchase.

He said 70% of his income goes toward his expenses - half goes toward his rent-controlled $2,700-a-month Napa apartment. "Homeownership is so out of my reach that I don't even consider it a realistic or attainable goal [for myself] in the US," Ceresia said.

Young millennials will likely bear the brunt of a slower job market

While older millennials may be more vulnerable in terms of building wealth, younger millennials, who experienced the Great Recession's recovery period and entered a better job market, would face a different set of challenges during a second recession - particularly in the job market and through income loss.

All experts I spoke with reiterated a typical effect of recessions: They tend to hit younger workers harder in the short term.

Heidi Shierholz, a senior economist and the director of policy at the Economic Policy Institute, said she anticipated a millennial age split in the job market. "The way a recession can really hurt people just starting out can have lasting effects," she said. "There's a lot of evidence that the first postgrad job you get sets the stage in some important way for later."

Millennials who are 25 and 35 are in different places in their careers, she said, as the latter is more established. "But if they don't have a job or get laid off, the hard thing about searching for a job during the downturn is that there are fewer available," Shierholz said.

And in a recession, companies might hire less than they usually do or not increase pay for employees, especially younger ones, said Winnie Sun, the managing director of Sun Group Wealth Partners.

Shierholz's and Sun's sentiments are already proving true: The economic freeze created by the coronavirus pandemic has led to a hiring freeze among many companies.

A recent study by the St. Louis Fed forecast that the wave of layoffs, if it continues unabated, could lead to 53 million Americans who want to work but are out of a job in the second quarter of 2020 - that would mean an eye-popping unemployment rate of 32%. For comparison, in 2009 at the peak of the Great Recession, unemployment rates stood at 10%.

Service-sector workers of all ages have so far borne the brunt of this economic toll, but a lower earning potential for millennials translates to less money to put aside for life goals. Sun cited the Great Recession as a prime example of the loss-of-income-to-wealth snowball effect: It caused people to rent longer and take on jobs below their education levels, thereby hampering their abilities to build wealth.

Consider Emily Baniak, 28, who entered college in 2009 with the dream of becoming an interior designer. She recalled that a professor, a former architect who had lost his job in the recent recession, told students that job security in the design industry relied solely on the economy.

Fearful that she had made an economically unsafe career choice, Baniak, upon graduation in 2013, accepted an offer to teach art at her former high school in Punta Gorda, Florida. To her, a secure job market was worth the switch - but it wasn't without its drawbacks.

"I cut my career short and took the safe route, and, unfortunately, it shows in my finances," she said. As a junior designer, she would have started out earning significantly less than she does now but would have had more opportunity for growth.

"I just received my first raise in seven years of teaching," she said. "Had I stayed in the interior-design industry, I could've potentially made up to $40,000 more per year than I do teaching."

Millennials are unlikely to shoulder a bigger student-debt burden, but a recession might slow their repayment

A slower job market isn't the only factor affecting the generation's ability to build wealth. Student debt, Sun said, is causing millennials to postpone large financial goals by a decade or more.

The national student-loan-debt total exceeds $1.5 trillion, and student-loan debt was at a record high of nearly $30,000 per borrower for the graduating class of 2018.

Philip Garcia, a 37-year-old millennial who studied business management, said the Great Recession hit him "particularly bad" because of student loans. He and his wife bought a small house in McAllen, Texas, in 2016, and they are years from paying off their mortgage.

"We'll buy the house when we're 90," he joked.

Garcia, who graduated in 2012 and now works in insurance, owes $57,000 in student loans. Nearly eight years out of college, he has so far been able to pay off only the interest.

Those born in the '80s, like Garcia, have some of the highest debt-to-income ratios, thanks to the combination of student loans and the dismal job market they entered. But experts said they didn't foresee another recession bringing massive changes in student-loan debt, though it could slow repayment. And as of March 20, the government had extended financial relief to federal student-loan borrowers during the pandemic by allowing them to suspend their monthly payments for at least 60 days and slashing their interest rates to 0%.

But unlike in the mortgage situation, Ricketts said, the vast bulk of student debt is guaranteed by the government. That means there's no possibility that it will bring down banks as mortgages and mortgage derivatives did in the Great Recession.

Emmons said that "if people lose jobs or take on debts, there will be a lot of individual pain, but it doesn't look like it would be a credit crisis the way other debts were in the past."

One typical byproduct of a prolonged recession is that more people enroll in higher education as job prospects dwindle, but this might not be the case if a coronavirus recession is short-lived. A cohort did so during the Great Recession, Emmons said, but some didn't complete their degrees.

According to 2015 statistics from the US Department of Education, this pattern comes with two troublesome outcomes. First, income and wealth levels among millennials without bachelor's degrees were lower than those with degrees. And the default rate among borrowers who didn't finish their degree was nearly three times as high as it was among those who did. It's this group that Emmons considers the most worrisome; if they lose a job, he said, another recession would be very painful.

The government is firefighting a potential 2020 recession, but millennials aren't holding their breath

In this uncertain economic climate where jobs are disappearing by the week, unemployment figures keep rising, and more and more states are issuing shelter-in-place orders, all the experts I spoke with acknowledged that their predictions were hypothetical. The next recession's impact ultimately depends on how this unprecedented scenario unfolds.

Ricketts said that while he never expected to see the economy on the steep decline it's experiencing, the road ahead is still unclear. If a recession were to happen, he said, it could be relatively short, as economic activity could "snap back."

He added that the policy response as of March had been more aggressive than it has been historically. The $2.2 trillion stimulus bill enacted on March 27 will send $1,200 checks to millions of Americans, provide zero-interest loans to small businesses, and expand unemployment benefits. It's a bad sign of the state of the economy, Ricketts said, but also a hopeful sign that some of the damage to younger generations - or any worker of any age, for that matter - might be offset.

"It's a different shock to the economy," he added. "It's tough not to be somewhat unsettled. I'm hopeful we won't see a prolonged economic effect, but we don't know a lot about how it will work out."

In the face of mass layoffs and a stock-market drop like the US saw in the second half of March, millennials "would be hit harder," Ricketts said, "because they would be restarting at a later age, with less working runway and more responsibilities."

Most of the experts I spoke with emphasized that while another recession would certainly be an obstacle for millennials still wrestling with the aftermath of the first recession, the opportunities and challenges they'd face would depend on their age. While the last recession made many millennials risk-averse and cautious with their money, it also taught them how to weather an economic storm - which may have made them ready for another one.

As for the millennials I spoke with, sentiments ranged from a sense of resignation to a feeling of being as well prepared for the future as possible.

Anderson, the former chef who ping-ponged between jobs for years, was laid off from his furniture-salesman job in January after working there for four months and is still living with his mom in Reading.

"I don't really see how it can get any worse, except for me being homeless," he said.

Others, though, said the Great Recession had actually helped them steel themselves for what lies ahead.

"If there's one thing I learned from the Great Recession, it's how to be financially secure," said Baniak, the art teacher, who has now made a smooth transition to virtual teaching. She added that it instilled in her a fear that she should always have money saved. With every paycheck, she puts "just enough" money in her checking account to cover bills; the rest goes toward savings.

If there's one thing I learned from the Great Recession, it's how to be financially secure.

She said she's terrified that the global economy will collapse but feels very little stress about her own job security and income. If a recession does strike, "I'm confident I would be well prepared," she said. "I wouldn't worry about losing my job. And if there is any reason to be thankful for the path I chose, it would be this."

Garcia, the insurance agent who lives in Texas, expressed a similar thought, even though his wife is currently the only one working because of the coronavirus pandemic and they just started collecting food stamps.

"I'm not nervous about it at all," he said. "I learned from the last one. I have a small rainy-day fund that can keep us going for enough time to scramble and pick up the pieces if everything crumbles."