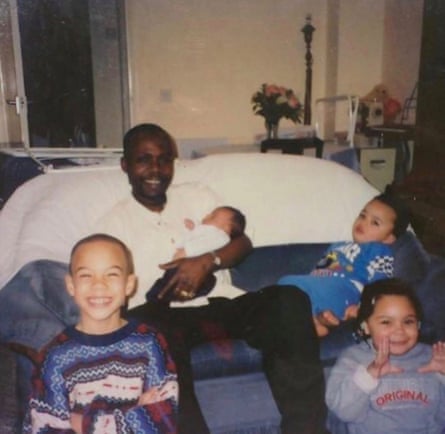

Kwajo Tweneboa adored his father. They were very similar: they both enjoyed a laugh, had an interest in current affairs and made sacrifices to care for others. Then, in January 2020, Tweneboa watched his father, who suddenly became terminally ill with cancer, die. All the while, cockroaches, mice and flies infested their dilapidated housing association flat on the Eastfields estate in Mitcham, south London.

Tweneboa, a 23-year-old student, shared the flat with his two sisters, 24 and 21. He says he asked the housing association, Clarion, to make repairs for more than a year, with little success, before deciding to take further action. Since then, he has become a champion for his neighbours and all those living in similarly squalid conditions, forcing landlords and housing associations to acknowledge their responsibilities and make urgent, necessary repairs.

“I’m willing to take on absolutely everyone and anyone to ensure this issue is spoken about,” he says. “It’s been going on for way too long.”

Speaking via a video call, Tweneboa is eloquent and passionate as he lists the appalling conditions his family had to endure after moving into the flat in 2018. He says the pest infestation made home cooking impossible, so the family lived on takeaways. There was mould on walls. In one room, there was no ceiling, just exposed beams and floorboards from the flat above. Cabinets rotted and water poured through light fixtures, which Tweneboa claims were surrounded by asbestos. “I couldn’t even bathe in my own house. I had to go to the gym,” Tweneboa says.

Despite repeated appeals to Clarion – Europe’s largest housing association – he says he received little help. (Clarion denies this.) When Clarion did respond, they sent the wrong people to fix the wrong thing. Tweneboa says he complained about the missing ceiling in February 2020, but no one came to fix it until October. “Instead, they sent a roofing team out – it was stupid things like that. They didn’t actually put the ceiling back up until the following year.”

Meanwhile, Tweneboa’s father, a former care worker, was undergoing treatment for stage 4 oesophageal cancer. He was diagnosed in November 2018, 10 months after they moved in, and cared for at home by Macmillan nurses. Tweneboa was shocked by his father’s sudden deterioration. “I’ve never experienced anything like that before,” he says. “He would just sleep for days on end. It wiped him out. I believe he deteriorated as quickly as he did as a result of the conditions he was living in.”

The nurses struggled to care for Tweneboa’s father due to the dire state of the property. “They were finding it difficult to bathe him in the bathroom, for example, as it had no lights and the tiles were falling apart.”

Landlords ignoring their tenants’ requests is an all-too-common practice. In October, the Housing Ombudsman’s report on damp and mould in socially rented properties found evidence of “maladministration” among 56% of the 142 landlords they investigated over a two-year period, rising to 64% for complaint-handling alone. The report said: “This failure rate was often the result of inaction, excessive delays or poor communication.”

The roots of Britain’s housing crisis can be traced to Margaret Thatcher’s government and the 1980 Housing Act, which gave council tenants the right to buy their council homes. Councils enticed tenants with the offer of 100% mortgages and generous discounts on the value of their property. Wealthier tenants were often able to transform their homes before selling them or becoming landlords themselves, but this resulted in a drop in the numbers of properties available for those who still required social housing.

Today, getting social housing – and having it repaired – can feel like a lottery. The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (now the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities) had its budget cut in half in 2010, while austerity has the housing departments of councils short-staffed and unable to respond quickly to complaints.

When Thatcher took power in 1979, the average council tenant paid £6.40 in rent a week. When John Major took office in 1992, tenants were forking out £30 a week – a rise of 370%. However, the average pay for full-time manual workers rose by only 189% over the same period, which means the proportion of income spent on rent by those workers had increased by about 62% by 1992. Councils have not replaced the properties they sold and many tenants who remain in social housing feel as if they have been forgotten.

The lack of social housing stock also forces many low-income households into the lower end of the private rental market, where they have even fewer rights than social renters, who can usually rent their homes for life. Assured shorthold tenancies allow private landlords to issue no-fault eviction notices without giving a reason, which means some landlords will ignore tenants’ complaints about essential repairs and address them at their own convenience – especially when dealing with low-income tenants who feel they have few options.

One of the critical problems with housing in the UK is that many of the buildings are old: 81% were built before 1990, 35% were built before 1945 and 20% were built a century ago. Austerity has compounded this to create the housing misery we see today. The Good Home Inquiry, published by the Centre for Ageing Better in September, found that 4.1m homes do not meet the decent homes standard (DHS), the statutory minimum standard for housing. This states that homes must be free of dangerous hazards, have modern facilities, be in a reasonable state of repair and have effective insulation and heating. Tweneboa’s home fell well short of these criteria.

Tweneboa and his sisters had lived with their father since they were children (his mother also lives in London). Before moving to Eastfields, they had spent years in cramped temporary accommodation, unable to afford the cost of a mortgage or the high rents of private accommodation. Once, they were housed in a one-room converted garage. “There was mould growing on to the beds and we had a water [pipe] burst during winter, so we had to call the fire brigade. It was just absolutely horrific.” Tweneboa’s father fought for years to get the family into social housing; Eastfields was the only permanent accommodation offered to the family.

A year after his father died, Tweneboa took matters into his own hands. In May, he decided to shame the housing association on Twitter, posting a collection of photos showing his family’s living conditions. He wrote: “Clarion Housing has to be one of the worst council housing in London. Since my dad passed away in 2020 they’ve left me in a property which has been described as ‘unliveable’ and when I’ve called to chase a leak which I reported 5 days ago they’ve told me they’re busy.”

The tweets went viral, attracting attention from the national press. Tweneboa also started a petition asking Clarion’s chief executive, Clare Miller, to resign. The petition noted how Miller was paid £400,000 a year while “her tenants live in conditions not fit for animals”.

The negative press appeared to spur Clarion into action. They repaired Tweneboa’s flat over the summer and issued an apology stating: “We acknowledge the inconvenience the repairs issues at this property have caused and apologise if Mr Tweneboa feels we haven’t provided the service expected from us.”

“That sentence really annoyed me,” Tweneboa says. “So I contacted every single house on my estate and, within half an hour, I had constant messages or photos, complaints of everyone else suffering with the same disrepair – in some cases, even worse.”

Tweneboa says he discovered that some tenants on Eastfields had been complaining about their living conditions for decades. A family of six complained they were contending with dampness so severe that mushrooms had sprouted all over their home. Other tenants reported collapsed ceilings, broken fire doors – which allowed strangers to trespass, use drugs and relieve themselves in the communal hallways – and hordes of mice scurrying around inside the walls.

Tweneboa posted a thread on Twitter with more photographs and descriptions of the disrepair, forcing Clarion to issue a further response: “We recognise that some repairs and pest control measures have taken too long over the last six months and apologise to all affected residents.” The housing association also promised “a continuing planned investment programme”, which included decorating and updates to appliances.

After he called out Clarion online, Tweneboa’s inbox blew up. “I’ve had hundreds, if not thousands, of people contact me from across the country,” he says. One family said they had to wash their children on their high-rise balcony during the height of winter because their shower had broken. Clarion allegedly told the mother of the family to use the toilet and the kitchen sink; her son ended up in hospital due to the cold conditions. A woman in Westminster claimed her water heating pipe exploded at 4am, flooding her flat and leaving her with burns. Tweneboa also heard from tenants struggling with mould, damp, disrepair, infestation and neglect.

“We’ve been suffering,” he says. “This should be a national scandal, but it’s been kept under wraps and ignored for so long. I’ve realised that this has been going on for absolutely decades, longer than I’ve been alive, but people in power just don’t care.”

In 2017, 72 people died in the Grenfell Tower fire. The disaster exposed the high level of neglect for the country’s poorest households and highlighted how slow landlords can be to react to serious complaints. Concerns had been raised about the materials used in the building’s external cladding years before the Kensington high-rise went up in flames. The catastrophe inspired books, documentaries and films and galvanised housing campaigners. Four years later, though, not much has changed for the UK’s poorest tenants.

Tweneboa says he thought that, after Grenfell, councils would be more conscientious about housing safety. “But what I learned is that people’s lives are still being put at risk. I have no doubt that people have died as a result of living in social housing.” His intuitions are correct. In 2019, E3G, a climate change thinktank, reported that 17,000 people died due to cold households in the winter of 2017/18 – the sixth-worst figure in a study of 30 European countries. Studies have shown that poor living conditions can have a profound impact on people’s physical and mental wellbeing.

Since its public shaming, Clarion claims to have knocked on the door of “each and every home” in Eastfields to inform residents of its plans for the area. It has also opened a new on-site office and announced a £1.3bn regeneration project in Merton, including the Eastfields estate.

A Clarion spokesperson says: “Clarion Housing Group and Merton council have a joint vision for the future of the Eastfields estate, which is a community that benefits from regeneration and brings forward hundreds of new affordable homes.

“Since Mr Tweneboa’s case first came to light last year, we have invested significantly into existing homes, apologised to residents where our service fell short and published a comprehensive lessons learned report. Our focus now is on the future and working with the council, our residents and key partners to create a community that everyone living in Eastfields will feel proud to call home.”

After everything Tweneboa has been through, does he feel as if he has made a difference? “My community definitely values me because of how outspoken I’ve been. But Clarion only put out their statements when I get the media involved. They’ve never been willing to talk to me directly. They don’t care. [But] I don’t need to feel valued by them; the only thing I care about is people who are suffering under the same conditions as I did.”

On the Eastfields estate, Clarion says it has completed more than 600 repairs since June 2021, as well as kitchen and bathroom replacements at 24 properties, as part of their investment programme. Although his father never got to see these achievements, Tweneboa knows he would be pleased to see him helping so many people. “He would be proud and he would say: ‘Keep going and keep doing it until they listen.’”