“Does he realise he’s talking to somebody who’s nearly dead,” Evelyn Lipmann asked her daughter, Kate, just before an interview with the Observer last week.

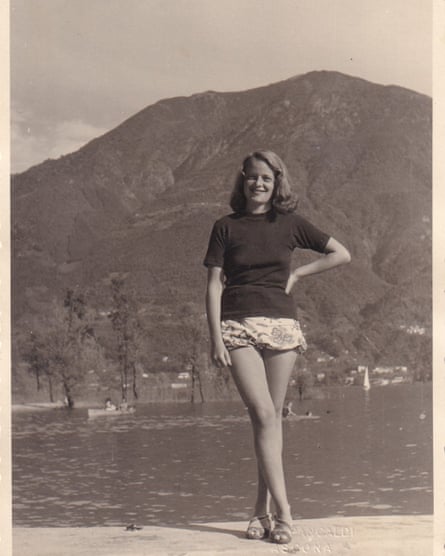

Very little about the 97-year-old’s wit and recall suggest the end is imminent, however, and her life story proves it would take a lot to kill her.

Born Evelyn Guttmann in Vienna, she survived four Nazi camps, including Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, and walked home across the wreckage of postwar Germany using only a page from a children’s atlas as a guide.

Three-quarters of a century after that feat, Lipmann relies increasingly on live-in care, but has been able to afford it and stay in her home of 64 years on the south-west outskirts of London, because of a little-known German-funded scheme which supports Nazi victims.

If her daughter had not spotted a small advert some nine months ago in the journal of the Association of Jewish Refugees (AJR) for the homecare scheme the association administers, the family could now be facing tough financial choices.

“It is quite extraordinary,” Kate said. “I just thought that sounds too good to be true, but I thought ‘well I’ll apply anyway’.”

Now she said her mother is “calmer about finances, and definitely has less stress”. “My family always helped me,” Lipmann said. “But I don’t have to worry about money like I used to, so it has made a tremendous difference.”

The AJR is concerned that there are hundreds of ageing refugees from Nazism in the UK, the last witnesses to the Holocaust, who could be suffering privation in old age because they and their families do not know about the scheme. “You could be looking at 1,000-plus people who could be eligible, but haven’t gone through the registration,” Michael Newman, the AJR’s chief executive, said.

He urged families with eligible relatives not to leave the application until live-in carers are needed, as the process of approval and verification takes months. “You can have people in their early 80s, fit and healthy and able, and the idea of registering and going through an application process for care is conceptually difficult for them to get their head around.”Newman said that, a few weeks ago, the AJR was in a race against time to help ease the final weeks of a 95-year-old man who had arrived in Britain on the kindertransport before the war. “There was this hour-by-hour effort trying to get into the system, so that he could benefit from some hours of care.”

This year, the AJR received just over £10m from the Claims Conference, established in 1951 to distribute funds from the German government to victims of the Nazis and to seek the return of Jewish property stolen during the Holocaust.

Of this year’s £10m grant, £8.5m is ringfenced for the homecare scheme. Covid and the winter have taken a toll among the beneficiaries, but there are currently 325 left – and many more could be benefiting.

After her needs were assessed, Lipmann was awarded more than 65 hours a week of care and the cost of a cleaner for up to four hours a week. On top of the German government-funded homecare plan, an Austrian-financed scheme pays for some other essential living costs.

Kate initially kept her application secret, in case it was too good to be true. Her mother agreed to the scheme after she was reassured on how it was funded. “She actually said: I do not want to have money from anyone in the UK, where other people are also in great need. But if it’s funded by the Austrians and Germans she was happier to take that funding, because it’s restitution,” Kate said.

Local authorities in the UK do provide financial support for care for the elderly. It is means tested (the maximum asset total allowed in England is £23,250) and though they are supposed to offer direct payments to help with live-in care at home, many councils are reluctant, despite the fact that it is often as affordable as a care home.

When awarding homecare hours, the AJR deducts any already being provided by the local authority. Homecare is more generous and faster than any authority scheme.

“Through Homecare – and the other programmes we operate – we are fortunately able to provide more and quicker alleviation,” Newman said.

The Guttmann family’s life in Vienna was torn apart after the Nazi annexation of Austria, the Anschluss, in March 1938. Lipmann was forced out of school. The Nazis took her father’s paint-making factory and forced the family out of their house. They were moved into the district of Leopoldstadt (the subject of a Tom Stoppard play last year) with other Jews. From there, they were deported to the Theresienstadt camp in Czechoslovakia, then to Auschwitz, then Bergen-Belsen.

“That was the first time I had any choice because the guards came and said: ‘You can go to a labour camp or go back to Belsen’ – and luckily I chose the work camp. I thought that while we’re working, the chances are they will keep us alive,” Lipmann said.

She and her mother were then sent as slave labour to make munitions at Salzwedel camp 140km south-east of Hamburg, where they were eventually liberated by the US ninth army in April 1945. They never found out what happened to her father, who had been separated from them on arrival at Auschwitz.

By the time of her liberation, Lipmann was suffering from typhoid and she had to be nursed back to health in a sanatorium before she and her mother could start the journey back to Austria.

“A German schoolgirl gave me a page from her atlas to give me an idea of what direction to go in. I had to go south, south, always walking, occasionally getting a lift,” she said.

It took another year before two aunts, who had already found refuge in Britain, could arrange passage for Lipmann and her mother.

One of those aunts lived in Walton-on-Thames, and that is where Lipmann still lives today in the house she moved into with her husband, Eric, as a young couple.

“The main thing is I am able to stay in my home with my family nearby,” she said. “That is wonderful.”

Enquiries about the AJR’s homecare scheme can be addressed to enquiries@ajr.org.uk, or on the website ajr.org.uk