Richard Nixon, a Republican president, apparently declared in 1971 that “we are all Keynesians now”. Mr Nixon seemed to admit that a serious shift in thought on the right of politics had occurred. But the decades of Thatcherism and Reaganism proved it to be a rhetorical move, not an ideological one. Rishi Sunak, the Conservative chancellor, attempted the same sleight of hand in last week’s budget.

Mr Sunak unveiled a national infrastructure bank and a strategy to tilt spending towards the north. He also repeated his March promise of £100bn in public investment. While the money, reorientation and the institution are welcome, they are less substantial and radical in scope than that prescribed by mainstream economics. This will lead to predictably poor outcomes for employment and GDP in the UK.

This is ideological. Mr Sunak will not invest on the scale that Britain desperately needs because it will risk his self-imposed borrowing limits. The Conservative manifesto in 2019 said that while the Treasury could borrow to invest, this could not exceed 3% of GDP on average. Mr Sunak’s splurge will come in under this rule. Given its historic levels of underinvestment, it is astonishing that the UK will invest less than the international average of 3.5%. Investment is crucial in any economic recovery from coronavirus and for dealing with the climate emergency.

State spending can play a central role by providing demand where the private sector cannot. It will create jobs in uncertain times. A recent report for the Institute for Public Policy Research reckoned that Mr Sunak is only providing a quarter of the boost it needs to stabilise the economy. Given the UK’s huge social and environmental needs, the thinktank suggests an investment stimulus to a Nordic 5% of GDP. The IPPR points out the government spending would catalyse corporate investment, currently a fifth lower than pre-pandemic levels. A major investment package that boosted jobs and growth would also see public debt as a proportion of GDP fall.

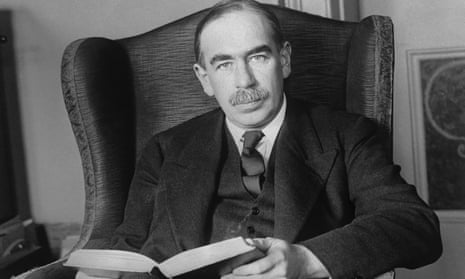

Lord Keynes’ work showed that there was a permanent role for government investment, as business would always invest less than it should because of uncertainty about the future path of growth. He also considered the market to underprice social and technological benefits. This led him to conclude that the state would take “an ever greater responsibility for directly organising investment”. This idea lay behind the Labour party’s plans, whose language Mr Sunak has lifted. They represented the right way to go. Private banks have a poor record in financing new investment, preferring instead to expand reckless consumption and casino-like speculation.

A national infrastructure bank could be a more “patient” investor to encourage innovation. But Mr Sunak has not said what his planned state bank will invest in. Neither is the Treasury being as creative as its counterpart in Germany, where a €100bn state fund can take “Covid” equity stakes in otherwise financially viable firms. In the UK, critics may claim that the state is bound to pick losers. The question is not whether the state picks losers, but whether government failure is better – or worse – than the market failure it seeks to correct. The chancellor is a Thatcherite at heart, but he would do better to keep Keynes in his head.