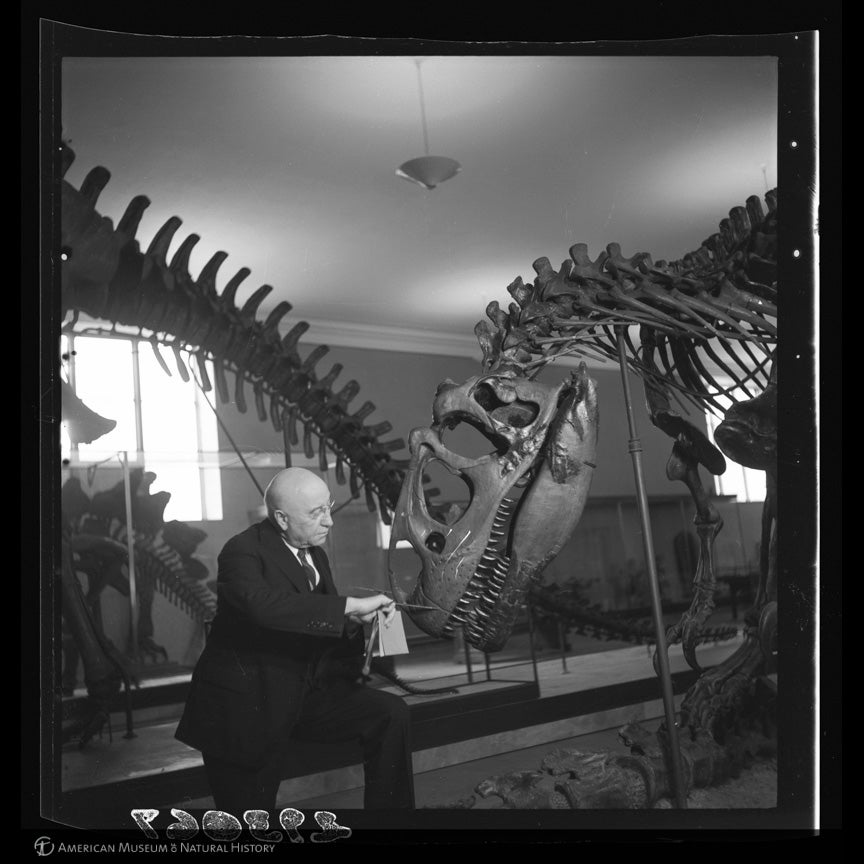

With its serrated teeth the size of bananas, massive jaws, and fearsome silhouette, the Tyrannosaurus rex looks like a child’s nightmare come alive. Since its unveiling to the public at the American Museum of Natural History in New York in October 1915, the T. rex has become the world’s most iconic dinosaur and sought-after museum piece, the one creature whose full Latin name is common knowledge. But behind its now-familiar stance lies a tale of heartbreak, pain, and long-delayed redemption.

At the story’s center was a man from the Kansas plains named Barnum Brown. He received his unusual first name after his parents sat in the kitchen of their farmhouse in 1873 puzzling over the question of what to call their newborn son. Hot with the memory of a recent trip to P.T. Barnum’s Great Travelling World’s Fair in his mind, his 6-year-old brother, Frank, burst in and yelled, “Let’s call him Barnum!” Though it carried a connotation of showmanship foreign to the flat surroundings, the name somehow stuck, and Brown soon passed the empty hours of his boyhood digging in the soil behind his father’s plows. The discovery of seashells some 600 miles from the nearest current ocean prompted Brown’s first interest in science, and with it came the realization that for him, a farm-oriented life dictated by the seasons was its own form of prison.

As soon as he was able, Barnum Brown escaped to the University of Kansas, where he joined digs at a time when the notion of going out into the field and intentionally unearthing dinosaur specimens was still a novelty. At the time, nearly all the most prized fossils known to science were found by accident, the product of either mining operations or wayward cowboys (the first Triceratops skull seen by professional paleontologists was found after a ranch hand lassoed it and dragged it behind him, thinking it was an escaped steer hiding behind a boulder). Yet the sense of being there at the beginning appealed to Brown, and he soon exhibited a preternatural ability to find fossils and extricate them from the earth without destroying them, leading to his receiving the nickname Mr. Bones.

The promise that Brown’s luck would not run out led Henry Fairfield Osborn, the head of the struggling American Museum of Natural History’s nascent vertebrate-paleontology division, to see in Mr. Bones a solution to his problems. The son of a powerful railroad executive, Osborn believed building a collection of dinosaur fossils would be his ticket to fame and influence worthy of his exalted family pedigree. Had it not been for his need for bones, Osborn, who lived in a Park Avenue mansion and counted Theodore Roosevelt among his childhood friends, never would have stooped to interact with a man whose boyhood was spent milking cows and collecting rocks. Yet Osborn had nothing but empty rooms where he hoped fossils would one day stand, and he turned to Brown to fill them. When Brown soon found a Diplodocus in Wyoming, the American Museum had its first dinosaur, and Brown and Osborn began an uneasy collaboration that would last for the rest of their lives.

Thanks to Osborn’s connections, Brown moved to New York and enrolled part time in a doctoral program at Columbia University. While living in a rooming house on Manhattan’s East 67th Street, he met a blond public school teacher named Marion Raymond who was finishing her master’s thesis. She was the daughter of a distinguished lawyer, a woman more comfortable with a book or in a laboratory than exploring the frontier; he was a farmer’s son who despite his brilliance and long career would never finish the doctorate, would author only two scientific papers, and could never abide the idea of staying in one place for long. Yet something about the two clicked, each finding in the other what they had been missing in themselves. Before long, the two married, and Brown began to feel the restlessness that had been a part of him since childhood seeping away, replaced with a sense of security in another person’s company.

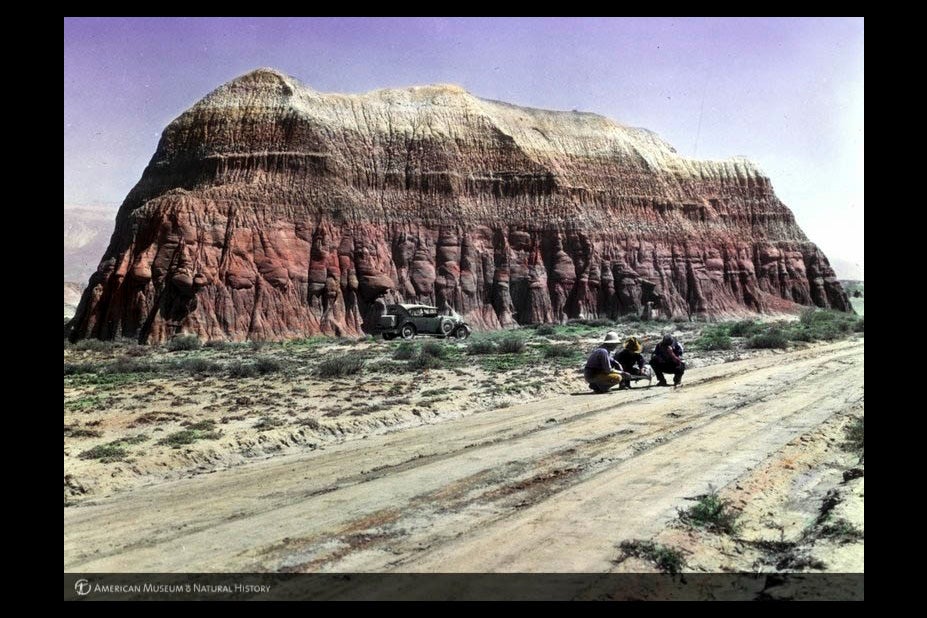

Yet he was often called away from home. At a time when the booming U.S. economy created previously unimaginable fortunes, dinosaur fossils became one of the trophies of the Gilded Age. Osborn pushed Brown to find larger and larger specimens, hoping that the sense of spectacle would not only bring in visitors but appeal to the ego of AMNH donors such as J.P. Morgan, as the museum competed against others backed by industrialists such as Andrew Carnegie in Pittsburgh and Marshall Field in Chicago. When prospectors working for Carnegie found an even larger Diplodocus, Osborn panicked and chided Brown for not finding it himself. In the summer of 1902, Brown ventured out into the Montana wilderness, fearing that failure to land a monster would mean the end of his career with the American Museum, and devour any dreams of starting a family with his new wife.

It was there, on the outskirts of Jordan, Montana, that Brown became the first human to lay eyes on the monstrous form of the T. rex. Everything about the beast seemed to strain the imagination: its jaws, so powerful as to explode the bones of its prey; its teeth, the longest of any known predator; its hips, leaving it 13 feet above the ground and capable of running at speeds over 20 miles per hour. “I have never seen anything like it,” Brown wrote in a letter that summer to Osborn.

Osborn finally had his prize. Yet when staff in the laboratory in New York began assembling the monster’s bones, Osborn deemed their quality and number insufficient for a proper museum exhibition and pressed Brown to find more. Once again, Brown set out into the wilderness, this time with Marion at his side. In the summer of 1905, Brown found two more T. rex specimens not far from where he made his initial discovery, in the Hell Creek Formation in Montana, making him—through a combination of luck and good timing—the only person to uncover the bones of the beast for nearly 40 years. The discovery prompted Osborn, who rarely left the luxury of Manhattan, to plan to meet Brown in the field. Only then did Brown admit that Marion was an unpaid and unacknowledged member of the expedition, and Osborn, generally not a fan of wives accompanying prospectors into the field, let the idea of visiting drop, without mentioning it again.

The public, of course, had no idea of the T. rex that Brown had uncovered. The bones of what would become the most recognizable creature on Earth sat in a laboratory high above the display halls at the American Museum for the next five years as a team of staff members completed the slow and deliberate process of removing every bit of stone and reassembling the creature into a lifelike form. In that time, Barnum allowed himself to transform from the prospector always in search of the next find into the outlines of a family man. Marion gave birth to their daughter, Frances, in 1908, and the Browns fell into an easy rhythm: Marion would take Frances for walks in a stroller through Brooklyn’s Prospect Park each day and return home in time to meet Barnum after he finished his daily work at the American Museum.

One sunny day in April 1910, Frances spiked a fever and broke out in a bright red rash soon after returning from the park. A day later Marion developed the same symptoms. Their fevers rose and rose again, unbroken by any remedy. (Penicillin, which we now use to treat scarlet fever, would not be discovered until 1928.) Barnum was left to frantically search for anyone who could help save his wife and their only child. He finally asked Osborn for help, hoping that his wealth could somehow save his family. But five days after entering Prospect Park a healthy young mother, Marion died on April 9, 1910. Frances soon recovered, leaving Brown to face the prospect of fatherhood alone.

It was more than he could handle. Within days, Brown left Frances with her maternal grandparents. While somewhat shocking to us now, newly widowed men leaving the care of children to others was surprisingly common at the time. Theodore Roosevelt, for example, left his infant daughter Alice with his sister and escaped to a ranch in the Dakota Territory after his mother and wife both died on Valentine’s Day 1884. Later, as an adult, Frances wrote in the third person: “Long afterwards, as a mature woman, Frances could understand how her father reasoned in that desperate time: a daughter was expendable, a wife was not.”

Brown lost the mooring in his life. With little direction left, he turned to the hardest work he could find, as if willing the elements to kill him. Within days, he left on a hastily planned trip to the Canadian outback. For the next several years, he roamed from Cuba to the Mediterranean to Asia, as if by constantly moving he would never have to stop and face his grief.

Osborn, meanwhile, used the bones of the T. rex for his own vile purposes. A racist who believed that Northern Europeans were a separate species that evolved independently of darker-skinned Africans, Osborn saw in the T. rex the perfect Darwinian fable, a hulking example of the physical power of untamed nature that went extinct from its lack of intelligence. (The theory that the impact of an asteroid crashing into Earth caused extreme changes in climate that killed nearly all dinosaurs—meaning that the T. rex’s brainpower, which researchers now believe was roughly that of a chimpanzee, had nothing to do with it—was not proposed until the 1950s.) In time, Osborn would use the popularity of the T. rex as the backdrop for a eugenics conference held at the American Museum, at which Leonard Darwin, the fourth son of Charles Darwin, would argue that through forced sterilization and the prevention of genetic mixing “the end of our species may be long postponed and the race be brought to higher levels of racial health, happiness, and effectiveness.”

When the T. rex was finally unveiled in 1915, it resonated with the public like no creature before it, the star whose name would forever be listed at the top of the marquee. The American Museum was overrun with letters asking how such a powerful creature could have gone extinct, while newspapers including the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times ran pieces focusing on the newfound sense that humans were diminished in the presence of a creature so menacing. The T. rex soon made the jump to Hollywood, where models of the dinosaur served as a villain in movies including 1925’s The Lost World—the first movie ever to be shown as inflight entertainment on a commercial airline, in 1925—and 1933’s King Kong.

Yet Brown was not on hand to revel in the acclaim. Instead, he remained in the field, long past the age when his contemporaries had retired to sedentary desk jobs. At one point, Brown alone had discovered more than half of the dinosaur specimens on display in the American Museum, along with fossils ranging from prehistoric horses to a piglike “oreodont” that went extinct 6 million years ago. Brown remarried a brash New York socialite named Lilian McLaughlin, who traveled the world with him, even as she recognized that he never lost his love for his first wife. Brown called out Marion’s name while he suffered delusions from a 106-degree fever induced by malaria while he was in Burma.

Frances, Brown’s daughter, lived her life in the shadow of her father’s discoveries. As a child, raised by her grandparents, she would often visit the museum and be taken on tours of the dinosaur halls by one of Brown’s assistants, as if trying to find some insight into her father through the fossils that he unearthed and shared with the world. As she grew older, she seemed to intentionally mold her personality in opposition to his: Where he was the life of the party, she was in a church choir; where he lived to roam, she became a college dean.

It was not until the frantic early days of World War II that Barnum—then working as a spy for the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency—would reunite with his daughter. They briefly lived together in her apartment in D.C., the first time they had shared a home since she was an infant, before Barnum once again left to chase the horizon.

Finally, as he neared retirement from the field, Barnum invited Frances to accompany him on one of his final journeys, an expedition to Guatemala. It was there that he shared a lifetime’s worth of gifts: a necklace from Turkey, tile from Mexico, untold stories of her mother on her wedding day. For the first time since Marion’s death, the two halves of Barnum’s life had come back together.

When, at the age of 89, he was asked to supervise the construction of nine life-size dinosaurs for a display at the 1964 World’s Fair, Barnum often commuted by limousine from Manhattan to Hudson, New York, where the models were assembled, with Frances at his side. Their conversations soon fell into unhurried moments, as he shared his life with her right as it was ending. “She never forgot the innumerable things he told her of his past exploits, nor his gleeful speculation about the probable reactions of onlookers when the dinosaurs were eventually floated down the Hudson River to the fair site,” Frances wrote.

The Monster’s Bones: The Discovery of T. Rex and How It Shook Our World

By David K. Randall. W.W. Norton & Company.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Barnum would not live to see it. He slipped into a coma and died on Feb. 5, 1963. His passing was noted in a short article in the New York Times, which called him the Father of the Dinosaurs.

The New York World’s Fair opened on April 22, 1964. It was an assault on the senses, the only event in history where a person could watch trained dolphins toss plastic oranges into an audience, catch a glimpse of the first Ford Mustang, and view Michelangelo’s Pieta within the span of a few minutes. For a moment, it was as if P.T. Barnum’s circus of novelties had been reborn for the modern age. And in the middle of the fair stood a 20-foot-tall celebrity. Fifty-nine years after Barnum Brown first discovered it in the Montana badlands, a modern monster reigned in the shadow of the Manhattan skyline: Tyrannosaurus rex.