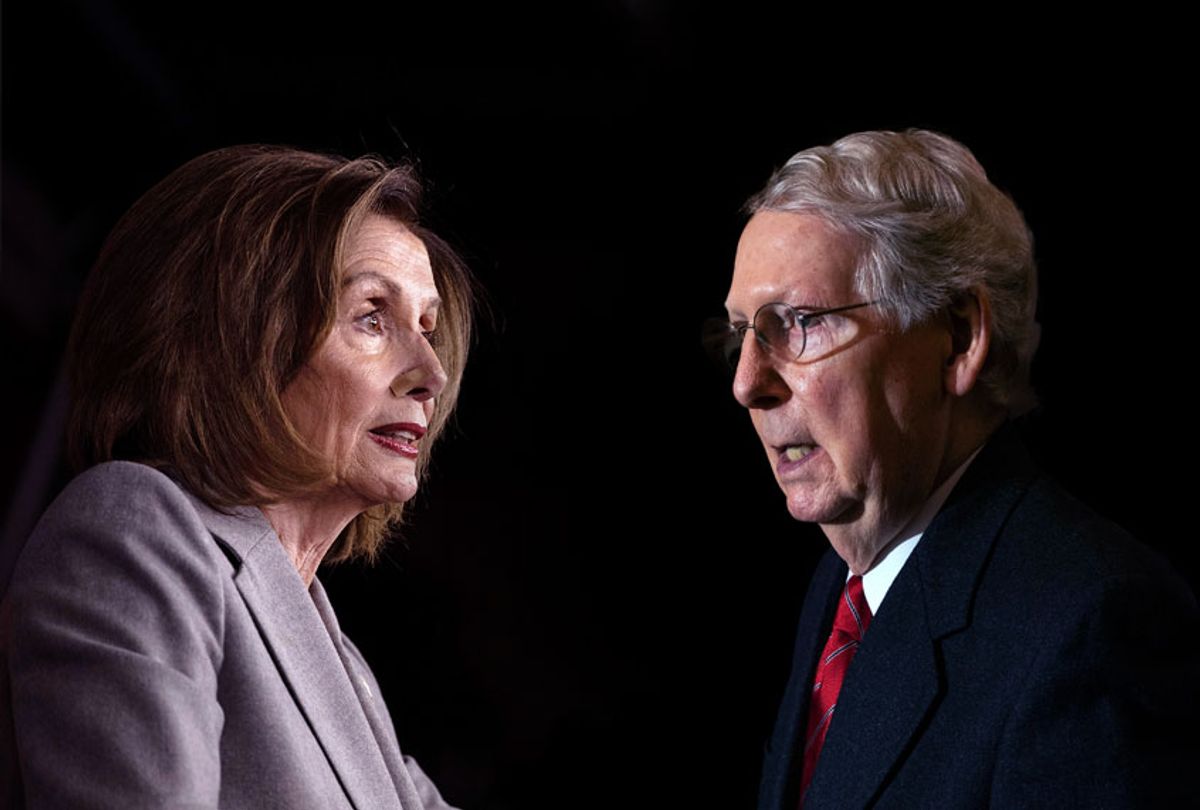

Hours after the passing of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg — and contrary to her dying wish — Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced that Republicans in the upper chamber plan to ram through a vote on her potential replacement before the end of Donald Trump's first term. Although he's been unable to muster the support of his GOP caucus for a new round of economic relief for millions of Americans during a pandemic, McConnell was quick to release a statement suggesting that Republicans have the votes to fill the most significant Supreme Court vacancy in recent history — and conceivably in the high court's entire history.

"President Trump's nominee will receive a vote on the floor of the United States Senate," McConnell vowed shortly after it was reported that Trump is expected to announce his choice within days. "In the last midterm election before Justice Scalia's death in 2016, Americans elected a Republican Senate majority because we pledged to check and balance the last days of a lame-duck president's second term. We kept our promise. Since the 1880s, no Senate has confirmed an opposite-party president's Supreme Court nominee in a presidential election year."

McConnell's rationalization is based on a lie, unsurprisingly. A Democratic-led Senate confirmed Justice Anthony Kennedy in 1988 during a tight presidential contest between Michael Dukakis and then-Vice President George H.W. Bush, after Kennedy was nominated by "lame-duck president" Ronald Reagan. What McConnell also didn't say is that Senate Republicans received 18 million fewer votes than Democrats in the 2018 midterms. Or that only after hours after Scalia's passing, 269 days before the 2016 election, McConnell said, "The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court Justice. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new President."

Nevertheless, it's "damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead" this time around. Unless a minimum of four Republican senators refuse to go along, there's little or nothing Democrats can do about it — short of shutting down the government by holding up a must-pass federal spending bill. Complaints of hypocrisy and sternly worded editorials about the "norms" of democracy won't move McConnell. It's not a question of if a vote will occur, only when.

With just 45 days remaining until the presidential election, McConnell's move may be the most consequential political decision in recent memory, and one that is certain to cement the Kentucky Republican's legacy of packing the both the Supreme Court and the entire federal judiciary with right-wing judges. Republicans hold a 53-47 majority in the Senate, and the only leverage liberals and progressives have is that several of those GOP senators are vulnerable to possible defeat this fall.

Sen. Susan Collins of Maine is still dealing with the fallout from voting to confirm Justice Brett Kavanaugh, and trails Democrat Sara Gideon in recent polls. There are several other Senate Republicans in tight races, including Thom Tillis in North Carolina, Joni Ernst in Iowa, Martha McSally in Arizona, Steve Daines in Montana, Cory Gardner in Colorado and even Lindsey Graham, who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee, in South Carolina. (Of those, Gardner, McSally and Tillis appear the likeliest to lose.) Early voting kicks off this weekend in as many as 20 states — but based on the public statements from Senate Republicans, at least some incumbents don't fear the potential electoral blowback of McConnell's decision.

"(If) it is a lame-duck session, I would support going ahead with any hearings that we might have," Ernst told Iowa PBS in July. "And if it comes to an appointment prior to the end of the year, I would be supportive of that."

McSally tweeted late Friday that "This U.S. Senate should vote on President Trump's next nominee for the U.S. Supreme Court." McSally has consistently run about 10 points behind her Democratic challenger, astronaut Mark Kelly, in the polls all summer. McSally lost her first race for Senate just two years ago (against Democrat Kyrsten Sinema) but soon thereafter was appointed by Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey to fill the seat left vacant after the death of Sen. John McCain. Her race is technically a special election, which could actually gum up McConnell's plans. If Kelly wins on Nov. 3, he could take office as early as the end of November, greatly narrowing the window for Republicans to approve a nominee during a lame-duck session. In the far less likely scenario that the Democrats win a special election for the Senate in Georgia (for the seat currently held by appointed Sen. Kelly Loeffler), the Republican majority would be reduced to 51 seats.

In other words, a lame-duck confirmation by the current Senate shortly after Election Day is the most likely timeline. While Trump and McConnell do not necessarily have their political calculations aligned, despite both being up for re-election, it's hard to imagine either the White House or the majority leader gaining anything from a record-breaking rush to confirm ahead of the election. Instead, Trump can dangle an anti-abortion, right-wing nominee to energize his base while putting off the controversial vote until after the election. Some Republicans, like Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas, are already arguing from an even more sinister position: Ginsburg's replacement must be seated on the bench in time for anticipated post-election litigation.

So far, Sen. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska is the only Republican who has publicly supported delaying a vote until after Election Day. "I would not vote to confirm a Supreme Court nominee. We are some 50 days away from an election," Murkowski told Alaska Public Radio. (She was the only Senate Republican who declined to vote for Kavanaugh's confirmation in 2018.) It would take three more Republican "no" votes to derail a confirmation, and there's no question that Collins, Gardner, Graham, Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa and a few other so-called GOP moderates will be subjected to intense lobbying from both sides.

Following Murkowski's statement, the Washington Post reported that McConnell had launched a pressure campaign to whip his caucus into silence, writing in a letter to Republican senators that "This is not the time to prematurely lock yourselves into a position you may later regret." That threat looks to have worked, so far.

The only hope Democrats have is to slow this train down.

If House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y. decide to fight this all the way, they could refuse unanimous consent on must-pass spending bills unless and until McConnell promises not to call for a vote until after the presidential inauguration on Jan. 20. Such a move would likely force Republicans to shut down the government, something they are usually more than willing to do. Democrats could also send the Senate new articles of impeachment against President Trump, which are privileged over judicial nominations in Senate proceedings.

Of course, in such a scenario McConnell would simply choose to fast-track another impeachment trial or vote to change Senate rules, as he did in eliminating the judicial filibuster. In strategic terms, that doesn't mean Democrats can't or shouldn't force him to do so. Republicans have absolutely nothing to lose in a December lame-duck session, especially if they know they have lost the Senate majority. But Democrats have an important chance to show their supporters that they understand the magnitude of the fight and have finally awoken to the reality that the opposition party will never play fair. It could serve as a harsh lesson for President-elect Joe Biden — assuming, of course, that the presidential election has been resolved and that he's the winner.

Perhaps the most important response Democrats have at this point remains further ahead: the possibility of expanding the Supreme Court by two seats, or conceivably more, once they hold a Senate majority. That remains a controversial tactic that until now has not had wide support among prominent Democrats — but in the face of what's about to happen that ma change.

If Democrats don't at least try to use every available tool to stop Trump's nominee from taking the bench before Inauguration Day, then there is no reason to believe they are prepared to respond to Republicans' blatant power grab. Democratic voters, as evidenced by record-breaking fundraising in the wake of Ginsburg's passing on Friday, are clearly spoiling for a fight. The New York Times reports:

Democratic donors gave more money online in the 9 p.m. hour after Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died — $6.2 million — than in any other single hour since ActBlue, the donation-processing site, was launched 16 years ago.

Then donors broke the site's record again in the 10 p.m. hour when donors gave another $6.3 million — more than $100,000 per minute.

Trumpists can control the national agenda for 45 more days, and Republicans will hold the Senate and the White House for two months after that, no matter what happens. It will take a new level of hardball from Democrats, far beyond anything they have mustered thus far, to prevent a historic Supreme Court power grab that will reshape the national agenda for a generation or more, long after today's political leaders have faded from the scene.

Shares