I’ve never not been small, and I’ve never thought much of it. Or rather: I never thought I thought much of it. What I thought I thought was: I’m 5 feet, 4 inches tall, and this is the body I’m in, these are the epiphyseal plates I was dealt, this is my angle on the world—and none of it defines me. I’m bigger than all that, I thought I thought.

I’m not saying I wasn’t aware. It’s impossible to be unaware, when you’re, say, walking against city crowds that don’t part for you the way they part for The Large. Or at parties. I’ve been 5-foot-4 at parties, I’ve been below the mating eye line in that tumbler of elbows and armpits, I’ve had to beckon people to bend over so they can hear my lame joke a second time. I’ve been a great noter of belt buckles, a great identifier with ottomans. And I can tell you, with great anecdotal confidence, that it’s all precisely what you’d expect/dread. Plunge yourself into a mass of pheromonally-redolent bodies at a low-ebb of collective inhibition, and trust me, you can feel the statistics come to life: Have you heard that hetero-aligned women would rather have a big man?

Not that I was paying too much attention. I was bigger than that.

When I was in my early 20s and something of an exercise buff, I joked to a male friend that my modestly swole chest might qualify me as a “gigolo” for “rich moms.” He answered, not joking, that there was no market for my stature among “rich moms” or, indeed, among any women. He suggested I offer myself to the bear market instead.

I’ve thought about that exchange ever since, and I’m not sure why.

I’m above it, after all. I have to be. If a man’s reach can’t exceed his husk (says the man with less husk), he’s probably a bust at being human anyway, right?

(And so what if he found himself mesmerized, for hours on end, by clips of Superman hitting monsters much, much bigger than Superman, and sending them hurtling off into the cosmos? That’s normal enough. Didn’t mean anything. Nobody wants to watch Superman hitting something smaller than Superman, obviously. That’d be pathetic.)

By my 30s, I was firmly installed in a world so dwarfed by giant buildings and enormous career aspirations and outsize personalities, height—I convinced myself—just wasn’t relevant. My “professional” world was at least a Kabuki of adulting, where money, talent, and wit shaped the mating-and-dating terrain for non-Adonises of every scale. And in all of those categories, I was solidly, safely in the lower-middle-of-the-pack—so I was fine, right? And sure enough, I led an undistinguished, mostly uneventful romantic life in New York City like thousands of other bespectacled media dweebs, tall and short. Career scuttled along. After a while, and enough spins of the wheel, I met someone wonderful. Got married. Had kids. Snuck my itty-bitty genes over the finish line, ensuring a new generation of underfolk.

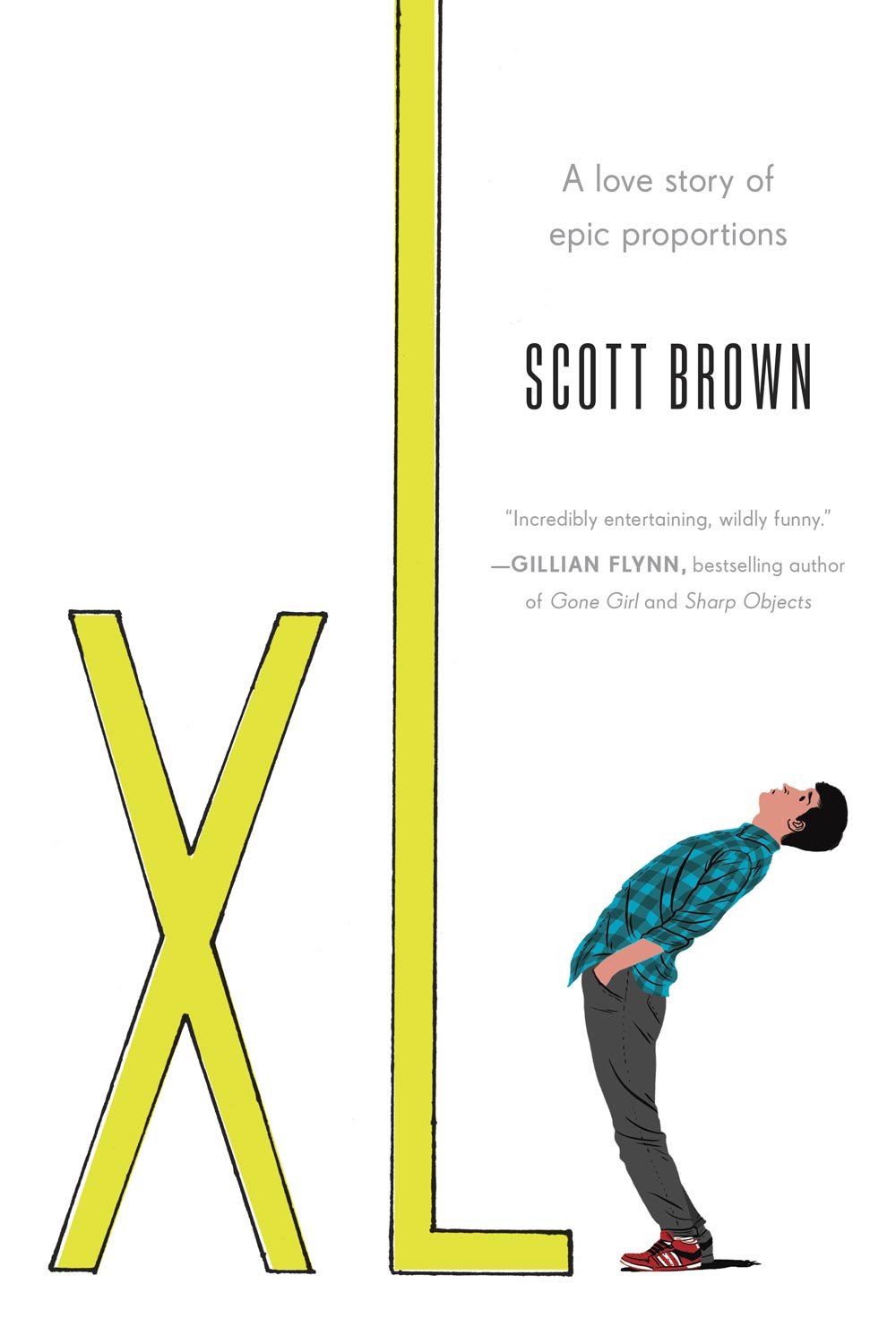

And then, last year, I found myself writing a young-adult novel about a short boy frustrated with his height. I didn’t come up with the idea; the premise and prompt came from a colleague. It never would’ve occurred to me. I’d never written for a specific physical body. All the white-guy heroes in my many previous, always-abandoned white-guy desk-drawer novels were of some indeterminate, wholly irrelevant middle height. They were just minds shambling along at mid-altitude. Pressed, I’d say I probably imagined them at 5-foot-8, average-ish. Existentially small, maybe, but physically? I wasn’t writing magical realism! No, my dudes were just mildly overeducated schmoes of median height in moderately amusing picaresques. Dwarfed by modern life, but not by, say, their girlfriends, or a lamp.

The point is, I even made my schmoes taller than I was. Never even noticed I was doing it, because I was so busy not-noticing how 5-foot-4 I was.

And then, last year, while writing that YA novel, microtragedy struck: I lost one-quarter of an inch.

I know people who could lose a quarter of an inch and not miss it. For these people—the lumpentall let’s call them—a mere 0.25 out of 72 or so is like losing a day’s interest on a solidly diversified family fortune. I’m not one of these people. Height-wise, I’m living hand-to-mouth and very close to the floor. The loss of that quarter-inch was meaningful. It threw my body mass index into yellow-alert territory. It occasioned casual doctortalk of “vertebral telescoping,” which I didn’t fully understand but sounded like bad news for a man of 5 feet, 4 inches.

Sorry: 5 feet, 3 inches.

I never knew how much I had invested in 5-foot-4, psychologically and self-image–wise, until it was gone—and yes, that’s got to be the saddest riff on a Joni Mitchell lyric ever committed to print. (Joni Mitchell is 5-foot-6, by the way, a damned giantess.) 5-foot-4 was my official, for-the-record, driver’s license–height for almost 30 years—and it turned out, a lie, a structural lie, longitudinal. All it took was one cold shaddak! of the stadiometer, one metallic tap to the top of my head, for a nurse practitioner to bring me crashing down to earth. Shouldn’t have felt like much of a fall. But it did.

Spinal Telescopy Theory notwithstanding, the most likely explanation for the loss of my quarter-inch was that I’d never had it in the first place. It turns out 5-foot-4 hadn’t been my height but my goal height, and I’d never reached it. Apparently, I’d been rounding up to the next inch since adolescence, and rounding-up-to-the-next-inch is so common among adolescent boys they strike it from the hippocampal record entirely. An aspiration that got fossilized into actuality, 5-foot-4 was revealed, decades later, as an asymptote, a horizon I’d never meet.

I was finishing a book about a kid who grows from 4-foot-11 to 7-foot-2 while coming to terms with being 5-foot-3 instead of 5-foot-4, and I had to ask myself, for the first time: What does being short mean? What if you really have to live in the body you’re dealt? Not just drive it like a rental?

“Short man” is not quite an identity. (Those standards are just too high, and the Twitter hours daunting.) Which leaves it stranded as mild insult, a rare 21st-century taboo. Today, we’re far more likely to grapple with “curvy women” than with tiny men. The latter are still a small tragedy. Napoleon complex, short-man syndrome, what have you—these are things the lumpentall don’t like to talk about. They’re also things they’ve confirmation-biased into existence because they find the anger of small men (q.v., children) more amusing/annoying than threatening/authoritative, and they need intellectualize their annoyance into a rationale: They’re just compensating, poor things. Let them simmer down.

Short Man is not an insult, or a syndrome, or a complex; but it is a mood. A set of suspicions, really: I’m not being looked in the eye. I’m not being treated as an adult. I’m being talked to like a child, I’m being taught, constantly. Science says we’re not angry little Pescis, but furtive hoarders. Science also offers something called Lateral Synovial Joint Loading, the intentional and strategic distressing of longbones to achieve extra length after maturation and fusion. Science sounds a little worried about us, like it’s worried we’re going to shoot someone at a poker game or take Austerlitz in a sneak attack.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

To me, none of this worry sounds super healthy. But it’s probably healthier and real-er than the blind retreat from my own flesh I embarked on for decades, a denial/decoupling/detachment so weightless it was practically an out-of-body experience.

At 5-foot-3 in middle middle-age, life about 50 percent spent, spinal-telescoping imminent, height set to dwindle from here on out, I’ve still got zero chance of earning money as a gigolo for rich moms but a decent shot at living in my body for the first time. Either because I’ve got more net confidence to combat panic or less net energy to spend on anxiety, I don’t need feel the need to rise above. Becoming comfortable with less is the business of getting old, or should be. I’ve got a hell of a head start.