The Book That Said the Words I Couldn’t Say

As a teen, I didn’t always know how to express myself. A now-forgotten novel helped me find my voice.

Updated at 1:24 p.m. ET on May 23, 2022.

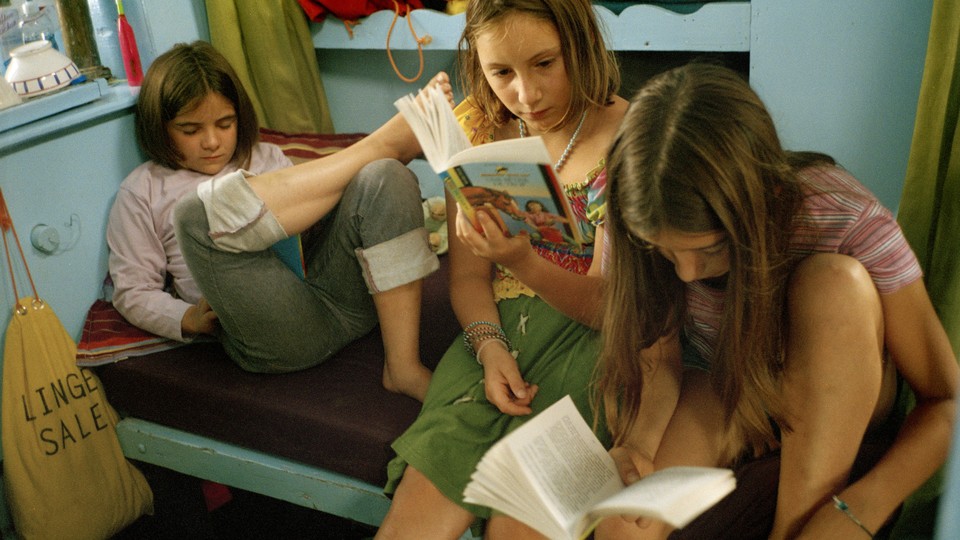

Coming of age in the early 1990s, I was part of the last cohort of teenagers to grow up without ubiquitous internet. We had pen pals and zines, but mostly we had one another. Girlhood was a time of endless phone calls with friends, though we didn’t always know how to put our feelings into words—and we couldn’t turn to Google to answer our questions. Books and mixtapes filled the gap between what we knew and what we could only intuit.

After reading Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse at a teacher’s prompting, I was awash with new perspectives on creativity and loss, while Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook made me only painfully aware that bitterness was something I had not yet earned. Then there were the classics of teenage girlhood that I passed among my friends, books that served as shorthand for my adolescent ennui: the poetry of Anne Sexton, Elizabeth Wurtzel’s Prozac Nation, Susanna Kaysen’s Girl, Interrupted, the “anonymous” fictional diary Go Ask Alice, and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar.

Out of sheer serendipity, when I was 16 years old, I found a brittle mass-market-paperback edition of Joanne Greenberg’s I Never Promised You a Rose Garden at a flea market in New Orleans’s French Quarter. Maybe what attracted me was the sinister cover illustration of a girl in profile framed by dark brambles, or perhaps it was Lynn Anderson’s 1970 country hit “Rose Garden,” whose lyrics echoed the book’s title. Regardless, I inhaled the book, looped a rubber band around the fragile jacket to keep it intact, and, as one did, promptly shared it with a friend.

The changing bodies, unexpected responsibility, and shifting circumstances of adolescent girlhood could make you feel like you were losing your mind. When I passed along my copy of I Never Promised You a Rose Garden, which centers on a teenage girl’s hospitalization with schizophrenia, to my friend, I wasn’t making a statement about depression or mental illness. I was trying to share the story of a girl like the two of us, who is scared and lost, but survives. Voices outside our immediate experience offered a lifeline; I felt like they could help me save someone from drowning when I didn’t know how to swim either.

Published in 1964 under a pseudonym and reissued this month, Greenberg’s I Never Promised You a Rose Garden is a fearless coming-of-age novel about Deborah Blau, a midwestern Jewish teenage girl in the 1950s. Like The Bell Jar, it tells the story of a young woman’s descent into mental illness and her attempt to recover, but Greenberg’s book eschews any element of glamour. The novel begins after Deborah’s failed suicide attempt, and takes place almost entirely within the numb, fetid, and frustrating confines of various psychiatric wards and doctor’s offices. There are no fashion-magazine contests, jobs in New York, or ballet tickets to be found.

The specter of displacement looms in Deborah’s life. Coming from a family of immigrants, she faces generational guilt and trauma, a history of childhood illness, and vicious, anti-Semitic peers. Her schizophrenia traps her between everyday reality and Yr, an imagined world complete with demanding gods and tormentors who speak a strange language. When real life becomes too much to bear, Deborah flees into Yr, which closes “over her head like water and [leaves] no mark of where she had entered.” But Yr is itself a terrifying prison. With the help of her therapist, Dr. Fried, Deborah strains to separate from this other world, where the “terror” has “no boundary.”

Abandoning childhood for adulthood can be shocking; in Deborah’s journey, perhaps I saw something like an excruciating version of that transition. She was relatable in other ways too. Unlike Plath’s Esther, Deborah isn’t ambitious, and she doesn’t care about being sophisticated; she seeks nothing more than to be free from her demons, to take pleasure in drawing and nature, and to be part of a community—in other words, to discover adulthood on her own terms. Although I didn’t experience mental illness, I struggled with the injustices and confusion of teenage girlhood. Every day I put on my school uniform and studied diligently, even if, sometimes, I felt like Deborah—desperate to calm a mind in revolt.

Eventually, Deborah emerges from the worst of her illness. Though Greenberg leans into depictions of Deborah’s erratic, violent behavior as well as the abuse perpetrated by the hospital’s medical attendants, her descriptions of life in the psychiatric ward are not relentless or excessive; she suffuses the narrative with a current of hope for a life outside the protected wards. Over the course of the novel, Deborah creates true connections with her fellow patients, and especially with Dr. Fried, building trust and devotion. The reality of her illness never disappears, but the pain subsides—gradually, much like any coming-of-age. “The bone-truth hurt, but a little less this time,” Greenberg writes.

I Never Promised You a Rose Garden was an enormous best seller and, in the decades that followed its publication, was celebrated along with other coming-of-age novels that grappled with teenage mental illness, such as The Bell Jar, which had been published a year earlier. Though these two works deal with similar themes, they had very different trajectories; Greenberg’s novel had slipped into relative obscurity when I discovered it cast aside in a bin of used books. Today’s teenagers have access to a much wider range of resources than I did to help them deal with the difficulty of adolescence. But they might still find something relatable, and useful, in books like Greenberg’s—which champions nonlinear journeys and tough, humane conversations about growing up. The enduring dignity it gives to so many facets of girlhood secures its place as a classic.

By the end of the novel, Deborah receives her GED and finds a delicate peace with her family. But the true prize that she gains from her hospitalization is Dr. Fried’s wisdom. In a moment of duress, she stresses to Deborah, “I never promised you a rose garden. I never promised you perfect justice … I never promised you peace or happiness. My help is so that you can be free to fight for all of these things.”

What Dr. Fried did for Deborah was to simply show up for her, even when no cure for her illness was likely. This lesson weighs on me when I think of all the things unsaid between teenagers. The friend to whom I lent this novel never returned it. We attended college, wrote letters, and grew apart. We got older, had daughters, and reconnected. The last time I saw her, we watched our children together on a playground. But I never asked if she’d read the book. Last summer, she died.

Describing Deborah’s recovery, Greenberg writes, “Because she was going to live, because she had begun to live already, the new colors, dimensions, and knowledges became suffused with a kind of passionate urgency … Now that she held this tremulous but growing conviction that she was alive, she began to be in love with the new world.” I like to think the crowded, vibrant life my friend lived means that she internalized Greenberg’s message. When I gave her this novel, all those years ago, I lacked the words to express myself. Death has created another gulf altogether. But I continue to take comfort in the power of Greenberg’s book—and others that I pressed into the hands of my friends as a teenager—to have said things I couldn’t say.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.