A strange puzzle has been taxing astronomers for many years: where are the hot Neptunes? For unknown reasons, there is an notable absence of planets the size of Neptune which lie close to their respective stars. Scientists looking for exoplanets often find hot large planets the size of Jupiter and “super-Earth” hot planets which are slightly larger than our planet, but they almost never find hot planets that are Neptune-sized. New research from astronomers at the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, may shed light on this oddity.

Using data from the Hubble Space Telescope, a few years ago the UNIGE astronomers discovered a warm Neptune-sized planet which was losing its atmosphere. The planet, GJ 436b, was shedding hydrogen from its atmosphere in a manner that suggested that the energy given out by nearby stars could effect the way that the planets evolve. And now the same team has discovered another warm Neptune, GJ 3470b, which is loosing its hydrogen 100 times faster than GJ 436b.

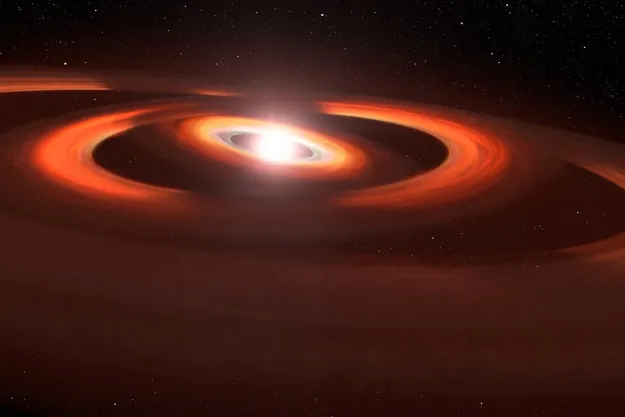

GJ 3470b is around 3.7 million kilometers from its star (around 2.3 million miles), which is just one-tenth of the distance between Mercury and the Sun. But the planet is loosing hydrogen at an even more rapid rate because its star is so young and energetic. The atmosphere of GJ 3470b is being lost fast enough that it will effect the way that the planet evolves, and the planet has already lost more than a third of its mass.

This finding suggests that hot Neptunes do form close to stars, but that the planets are rapidly eroded down to smaller Earth-sized planets or are even degraded completely until all that remains is a rocky core. “Until now we were not sure of the role played by the evaporation of atmospheres in the formation of the desert,” said Dr. Vincent Bourrier, researcher in the Astronomy Department of the Faculty of Science of the UNIGE. “This could explain the abundance of hot super-Earths that have been discovered,” confirmed David Ehrenreich, associate professor in the astronomy department of the science faculty at UNIGE.

In order to confirm whether this theory is correct, the researchers need to observe more exoplanets. The challenge is that escaping hydrogen can only be observed if the planets are less than 150 light-years from Earth, so the team plans to look for evidence of atmospheric escape of heavier elements such as carbon.

Editors' Recommendations

- Small exoplanet could be hot and steamy according to Hubble

- See the weather patterns on a wild, super hot exoplanet

- Hubble snaps an autumnal nebula glowing orange from young, hot stars

- Clouds on Neptune might be created by the sun, strangely enough

- Hubble watches an extreme exoplanet being stripped by its star