The original plans for New York City's Central Park included a Paleozoic Museum at 63rd Street and Central Park West, which would have displayed life-size concrete models of dinosaurs placed in carefully designed dioramas. Those plans were dashed in 1871 when vandals broke into the workshop of the museum's designer, Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, and smashed the models with sledgehammers, burying the rubble in the southwestern corner of the park.

The traditional take in paleontology circles is that the man behind the destruction was William "Boss" Tweed, who pretty much ruled the city's Democratic Party political machine at the time with his cronies at Tammany Hall. But a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the Geologists' Association identifies a different culprit: a lawyer and businessman named Henry Hilton, a member of the Tammany Hall contingent who championed plans for what would become the American Museum of Natural History.

Co-authors Victoria Coules and Michael Benton of the University of Bristol in England also found no evidence of a religious motivation for the destruction, i.e., opposition to the then-nascent field of paleontology and its associated implications for evolutionary theory, which were deemed "blasphemous" by some religious leaders. Rather, it seems to have been one of many "crazy actions" by Hilton. "We find that Hilton exhibited an eccentric and destructive approach to cultural artifacts, and a remarkable ability to destroy everything he touched, including the huge fortune of the department store tycoon Alexander Stewart," Coules and Benton wrote. "Hilton was not only bad but also mad."

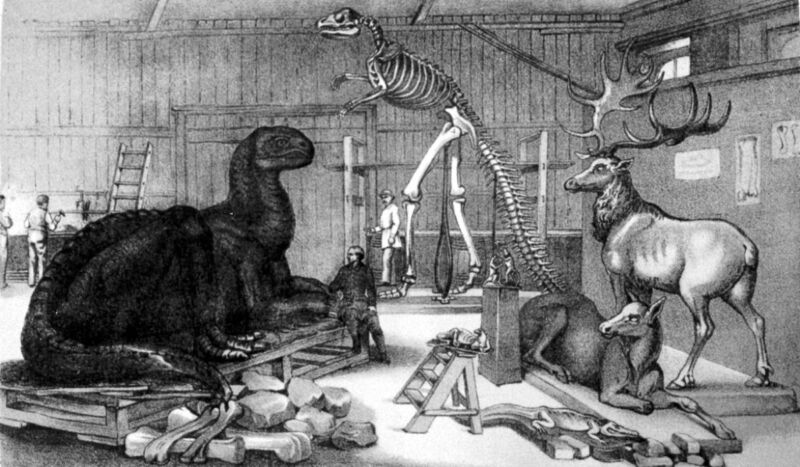

Hawkins was an English sculptor and natural history artist who caused a sensation at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London with his life-size dinosaur models. Cast in concrete and designed in conjunction with paleontologist Sir Richard Owen, the models were subsequently relocated to what is now Crystal Palace Park. Owen even hosted a memorable dinner party on December 31, 1853, inside the actual mold Hawkins had used to cast the Iguanodon sculptures.

News of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs spread to America and the Board of Commissioners in charge of developing plans for Central Park, led by Andrew Haswell Green. Hawkins was already in the US on a lecture tour, as well as designing and casting a nearly complete Hadrosaurus skeleton for the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia—the world's first mounted dinosaur skeleton. So he was a natural choice to create life-size dinosaur sculptures for the planned Paleozoic Museum in Central Park. Green wrote to Hawkins in May 1868, offering him the commission, and Hawkins accepted. The Board also tapped architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux to design the park's layout and features.

The dinosaur models for the Paleozoic Museum would be based on those specimens specifically found in North America, although this was just before the famous American "bone rush" of the 1870s to 1890s yielded large numbers of fossilized dinosaur skeletons and bones. Hawkins was provided a workspace in a large brick building known as the Arsenal (or the Armory) on 64th Street, beginning with small clay models based on the available fossil evidence before making the life-size molds. Meanwhile, Olmsted and Vaux lodged their architectural plans for the museum building and dug out the foundations.

Alas, the political winds were shifting in New York City by 1870. Boss Tweed disbanded the board led by Green and appointed a new board with all his own people, headed by Peter Sweeny, with Hilton serving as treasurer. By this time, plans were underway for the more ambitious American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) to be located on or adjacent to Central Park. Hawkins had to move out of the Arsenal into a nearby shed to continue his work to make room for the specimens and collections being acquired for the AMNH.

The AMNH wasn't intended to rival the planned Paleozoic Museum; Green's board had supported both projects. But Tweed's newly appointed board felt differently and elected to stop the project in May 1870. The official reason was economic. Their 1871 annual report specifically cited the high cost of completing the Paleozoic Museum (some $300,000, or about $7.5 million today), all coming from public funds, unlike the AMNH, which was supported by philanthropic fundraising. This was deemed "too great a sum to expend on a building devoted wholly to paleontology—a science, which however interesting, is yet so imperfect as not to justify so great a public expense for illustrating it." There were also plans for a zoo in Central Park, and the board favored supporting living animals over extinct ones.

reader comments

30