Developing an HIV vaccine has been notoriously difficult. The virus has been in human populations for over 40 years and still progress has been slow. One of the main reasons is that HIV is incredibly diverse — there are many strains circulating among humans, and the virus mutates at an extremely high rate.

Therefore, researchers are struggling to hit a highly variable, moving target. Further complicating matters is the fact that HIV attacks the immune system itself.

Kevin Saunders, first author of a new paper published in Science Translational Medicine describing a new HIV vaccine, has been studying this problem for over a decade. According to him, the immune system does have a mechanism which could target the highly diverse set of HIV strains, a type of antibody known as broadly reactive antibodies. Unfortunately, these antibodies are rare.

“The immune system naturally doesn’t make them at a high level,” explained Saunders, “because these antibodies have weird or uncommon features that make them more difficult for the immune system to make.”

The challenge then is finding the right vaccine target that stimulate this rare response in humans.

Coaxing the production of rare antibodies

As Saunders explains it, they are attempting to guide the body’s immune system in a direction it doesn’t normally want to go. Not only are these antibodies rare, but the body also tries to eliminate them because they run the risk of targeting the body’s own tissue.

To find a vaccine target that provokes the production of these antibodies, Saunders and colleagues turned to patients who have naturally mounted this response. Some patients do produce neutralizing antibodies against the envelope in which the virus exists, so the team isolated proteins from the viral envelope of the strain circulating in these patients.

“We can identify envelopes that react with the antibodies, and hope that if we immunize with those same envelopes, we will generate the same type of broad neutralizing antibody response,” said Saunders.

Armed with this vaccine target, the team immunized 22 rhesus macaques and saw a polyclonal antibody response, meaning the animals were generating multiple neutralizing antibodies targeting several sites on the viral envelope.

One of these was a site called CD4, which is an important finding because this site exists on many strains of HIV, and it is critical for the virus to bind to and enter cells. “If you can cover that site up with antibodies, you can block access of the receptor for that particular part of the HIV virus,” said Saunders.

Next, they measured the level of antibodies produced and grouped the animals into two groups. The animals which produced the highest levels of antibody were deemed high responders and the rest, low responders. Both groups were then given a simian HIV virus, a type of HIV that only infects primates, that has been designed to use the envelope protein from the human strain found in the vaccine.

A threshold for protection

Among the seven macaques deemed high responders, no detectable virus could be found after being infected with the simian HIV, indicating the vaccine protected them against infection.

“So not only did they generate neutralizing antibodies, but they were also protected,” said Saunders, adding that “we found that protection correlates with the amount of neutralizing antibody that they generate.”

After some mathematical modelling, Saunders believes they now have an idea of how much antibody is required for protection. This predicted protective level will now serve as a benchmark for human efficacy trials.

In the upcoming human trials the team will be watching to see if participants generate the predicted level of antibodies needed for protection and as Saunders explains they still need to broaden the specificity to other strains.

“The antibodies that we found here react great with the vaccine, they can neutralize the virus that corresponds to the vaccine, but they still need some work to become the broad neutralizing antibody that we’re ultimately trying to target.”

Reference: Kevin Saunders, et al. Stabilized HIV-1 envelope immunization induces neutralizing antibodies to the CD4bs and protects macaques against mucosal infection. Sci Transl Med (2022). doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abo5598

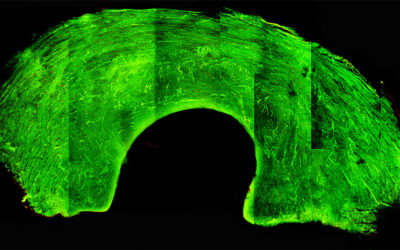

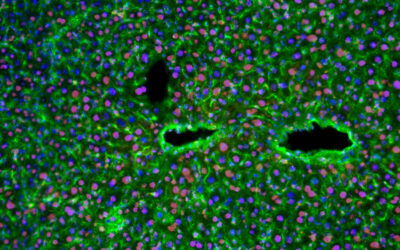

Feature image: National Cancer Institute