India is on its way to expand its “vaccine basket.” But is it too little too late?

The central government announced a change in its policy yesterday (April 13), under which Covid-19 vaccines that have received emergency approval elsewhere in the world would be fast tracked in India. Approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, or Japan’s Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency Japan would grant vaccine makers faster approvals in India. Additionally, those vaccines that are listed in World Health Organization’s “(emergency use listing) may be granted emergency use approval in India,” the health ministry said in a press release.

The first 100 recipients of such vaccines will be monitored by the authorities for side effects for seven days before these are opened up for the general public.

This is a major shift in India’s stance so far, where it had preferred vaccines manufactured in India, and had made it mandatory for foreign-made vaccines to conduct local, bridging trials in the country.

This new policy potentially opens the door for Covid-19 vaccines from Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson. The country has already approved the Russian Sputnik V vaccines, which have tie-ups with local pharmaceutical companies for production in India. “We hope and we invite the vaccine makers such as Pfizer, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson, and others…to be ready to come to India as early as possible,” Vinod Kumar Paul, chairperson of India’s expert group on vaccines, said during a press briefing.

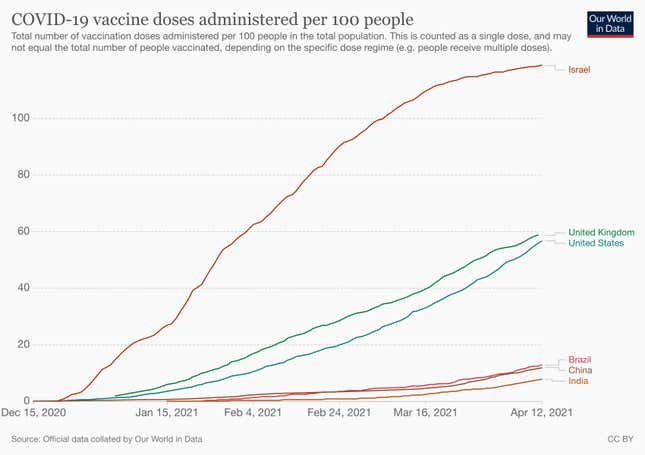

Such a policy shift comes from the alarming Covid-19 numbers in India. Yesterday (April 13), the country saw an all-time-high of 185,000 new Covid-19 cases, the highest single-day jump in any country in the world.

A raging second wave of the pandemic has also coincided with acute vaccine shortage in the country, forcing several centres in states like Maharashtra, Odisha, and Chattisgarh to halt the inoculation drive.

But is this renewed interest in foreign-made vaccines enough?

India’s stance on Pfizer

Pfizer was among the first companies to apply for an emergency use authorisation in India, back in December. At the time, Serum Institute of India’s Covishield, which is essentially the AstraZeneca vaccine, and India’s homegrown Covaxin had also applied for approvals.

A big hurdle in granting Pfizer an approval was the fact that its vaccine needs to be stored at ultracold temperatures, needing a specific cold storage mechanism that had limited availability in India.

At the time, the government had insisted on Pfizer’s bridging study in India, and the pharmaceutical company wanted India to first commit to buying the shots. Eventually, Pfizer withdrew its application in February.

Similarly, India’s subject expert committee had deliberated for several months before granting Sputnik V, an emergency approval, even though the Russian vaccine maker had tied up with India’s Dr Reddy’s Laboratories for local trials. Unlike Covaxin, whose phase III data are yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, both Pfizer and Sputnik V have established efficacy of over 90%.

Just days before allowing foreign-made vaccines to be imported, the government had a strong stance against it.

Shifting stance on importing vaccines

In a letter to prime minister Narendra Modi on April 9, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi had appealed that approvals be granted to all other viable vaccine candidates and that the drive be opened up for younger age groups.

At the time, Ravi Shankar Prasad, India’s minister for law & justice, and communications and information technology, hit out at Gandhi for being a “lobbyist” for pharmaceutical companies.

In four days, though, the government made a complete U-turn and said that it was going to make sure all priority groups receive the vaccine. India has set itself a target of vaccinating 300 million people, including healthcare and frontline workers, by August.

But thus far, it has not made its vaccine procurement public, barring the lots of Covishield and Covaxin that it has purchased in the past three months. In January, the government bought roughly 15 million doses of the two vaccines, a majority of which were Covishield. In March, it bought 100 million shots of Covishield and 20 million doses of Covaxin.

To inoculate 300 million people, India would need 600 million doses of any of the two-dose Covid-19 vaccines.