The practice of herbal medicine in Japan is known as Kampo, and such treatments are often prescribed alongside Western medicines (and covered by the national health care system). The first person to teach traditional Chinese medicine in Japan was an 8th-century Buddhist monk named Jianzhen (Ganjin in Japanese), who collected some 1,200 prescriptions in a book: Jianshangren (Holy Priest Jianzhen)'s Secret Prescription. The text was believed lost for centuries, but the authors of a recent paper published in the journal Compounds stumbled across a book published in 2009 that includes most of Jianzhen's original prescriptions.

"Before the book Jianshangren’s Secret Prescription was found, everyone thought it had disappeared in the world," Shihui Liu and his co-authors at Okayama University in Japan wrote. "Fortunately, we found it before it disappeared completely. It has not yet been included in the intangible cultural heritage. As we all know, intangible cultural heritage itself is very fragile. Everything has a process of generation, growth, continuation, and extinction, and the remains of intangible cultural heritage are also in such a dynamic process. We hope to draw more people’s attention to protect many intangible cultures that are about to disappear, including Jianshangren’s Secret Prescription."

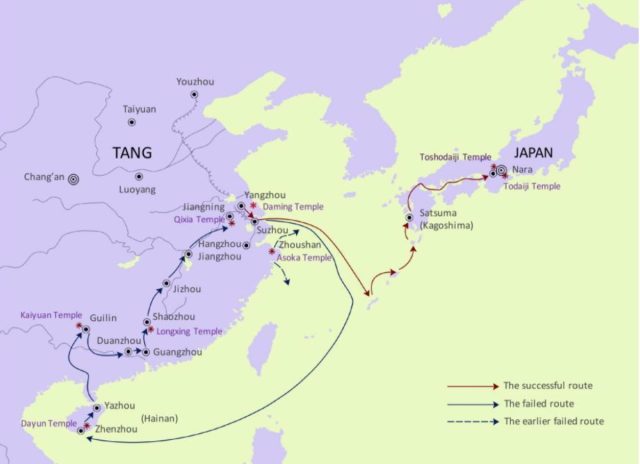

Born in what is now Yangzhou, China, Jianzhen became a disciple of Dayun Temple at 14 years old, eventually becoming abbot of Daming Temple. He was also known to have medical expertise—passed down from monks to disciples for generations—and even opened a hospital within the temple. In the fall of 742, a Japanese emissary invited Jianzhen to lecture in Japan, and the monk agreed (although some of his disciples were displeased). But the crossing did not succeed. Nor did his next three attempts to travel to Japan.

On Jianzhen's fifth attempt to go to Japan in 748, he made a bit more progress, but the ship was blown off course by a storm, and he ended up on Hainan Island. The monk made the arduous journey back to his temple by land, lecturing at monasteries along the way. It was nearly three years before he got back, and by then, he had been blinded by an infection. The sixth attempt, however, proved successful. After a six-month voyage, Jianzhen made it to Kyushu in December 748, reaching Nara the following spring, where the monk received a warm welcome from the emperor.

According to the authors, Jianzhen brought many traditional ingredients with him to Japan, including musk, agarwood, snail, rosin, dipterocarp, fragrant gall, sucrose, benzoin, incense, and dutchman's pipe root, as well as honey and sugar cane—all of which formed the basis for some 36 different medicines. He also managed to collect other ingredients over the course of his journey from China to Japan.

After settling in at Toshodaiji Temple, the monk began growing medicinal herbs in a garden, distributing his medicines to those in need—including Emperor Shomu and Empress Komyo. Despite being blind, Jianzhen could still rely on smell, taste, and touch to identify the various medicines. And he taught many Japanese how to collect and make those medicines, too. In fact, many Japanese medicines were once wrapped in paper decorated with a portrait of Jianzhen.

reader comments

90