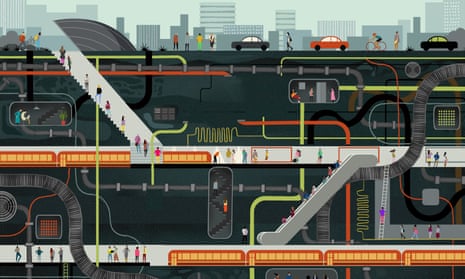

You can find signs of it everywhere you go. Step out of your front door and feel beneath your feet the thrum of tube tunnels and electric cables, mossy aqueducts and pneumatic pipes, all interweaving and overlapping like threads on a great loom. If the surface of the Earth were transparent, we’d spend days on our bellies, peering down into this marvellous layered terrain. But for us surface dwellers, going about our lives in the sunlit world, the underground has always been invisible.

In its obscurity, it is our planet’s most abstract landscape, always more metaphor than space. When we describe something as “underground” – an illicit economy, a secret rave, an undiscovered artist – we are typically describing not a place but a feeling: something forbidden, unspoken, or otherwise beyond the known and ordinary.

Our most celebrated explorers venture out and up: we have skipped across the Moon, guided rovers into Martian volcanoes and charted electromagnetic storms in distant outer space. Inner space has never been so accessible, yet geologists believe that more than half of the world’s caves are undiscovered, buried deep in impenetrable crust. The journey from where we now sit to the centre of the Earth is equal to a trip from New York to Paris, and yet the planet’s core is a black box, a place whose existence we accept on faith. The deepest we’ve burrowed underground is the Kola borehole in the Russian Arctic, which reaches 7.6 miles deep – about 0.2% of the way to the centre of the Earth.

The underground is our ghost landscape, unfolding everywhere beneath our feet, always out of view. But as a boy, I knew that the underworld was not always invisible – to certain people, it could be revealed. The summer I turned 16, when my world felt as small and known as the tip of my finger, I discovered an abandoned train tunnel running beneath my neighbourhood in Providence, Rhode Island. I’d heard about it first from a science teacher at school. The tunnel had once served a small cargo line, he’d told me, but that was years ago. Now it was a ruin – full of mud and garbage and stale air and who knew what else.

One afternoon, I found the entrance, which was concealed under a thicket of bushes behind a dentist’s office. It was wreathed in vines and had the date of its construction, 1908, engraved in the concrete above its mouth. Along with a few friends, I climbed underground, our flashlight beams crisscrossing in the dark. The mud sucked at our shoes and the air was boggy.

On the ceiling were clusters of pearly, nipple-like stalactites that dripped water down onto our heads. Halfway through, we dared one another to switch off our lights. As the tunnel fell into perfect darkness, my friends whooped, testing the echo, but I held my breath and stood completely still, as though, if I moved, I might float right off the ground.

That night at home, I pulled up an old map of Providence. I started with my finger where we’d entered the tunnel and moved it to where it opened at the other end. I blinked – the tunnel passed almost directly beneath my house.

That summer, on days when no one else was around, I’d put on boots and go walking in the tunnel. I couldn’t have explained what drew me down, and I certainly never went with any particular mission. I’d look at the graffiti or kick around empty bottles. Sometimes I’d turn off my light, just to see how long I could last in the dark before my nerves started to bristle.

To the extent that I was aware of myself at all, as a 16-year-old I sensed that these walks were outside of my character. I was an uncertain teenager, scrawny, gap-toothed, with librarianish glasses. When my friends were starting to make out with girls, I still had a terrarium of pet tree frogs in my bedroom. I read about other people’s adventures in books, without ever thinking to embark on my own. But something about the tunnel got under my skin: I’d lie in bed on some nights just imagining it running under the street.

Years passed and I forgot about those underground walks. I left Providence, went to college, moved on. But my old connection to the tunnel never quite disappeared and much later, following a series of unexpected encounters with the underground of New York City, my old memories re-emerged.

It began the first summer I lived in New York, when I was working at a magazine in Manhattan and living in Brooklyn with my aunt, uncle and two cousins. After years spent as a teenager, envisioning myself as a New Yorker, I had arrived to find the city impenetrable. I shrank in crowds and got off at the wrong subway stop, only to wander through Brooklyn too embarrassed to ask for directions.

Late one night, I was waiting for the subway in Lower Manhattan, on one of the deep-set platforms where on summer nights you can almost smell the city’s granite bedrock, when I saw something that baffled me. From the darkness of the tunnel materialised two young men: they wore headlamps and their faces and hands were black with soot, as though they’d been climbing for days through a deep cave. They walked quickly up the tracks, clambered onto the platform right in front of me and vanished up the stairs. I rode the train home that night with my forehead pressed against the window, fogging the glass, imagining a whole secret honeycomb of spaces hidden beneath the streets.

The young men in headlamps were urban explorers, part of a loose confederacy of New Yorkers who’d made a hobby of infiltrating the off-limits and secret spaces under the surface of the city. Some were historians who documented the grandeur of the city’s forgotten places; others were activists who trespassed to symbolically reclaim New York’s corporatised areas, or artists who assembled secret installations and staged performances in the city’s obscure layers.

In those first weeks, as I puzzled my way through New York, I found myself staying up late studying explorers’ photographs of hidden places: subway stations abandoned for decades; deep-valve chambers in the water system; derelict bomb shelters coated in dust – all of which felt as mysterious as lost sea monsters under the ocean.

One night, while sifting through an explorer’s archives, I was startled to find myself looking at a photograph of the tunnel I’d explored as a boy in Providence. I hadn’t thought about it in years: the single rail receding into the dark, the 1908 carved above the entrance. The photographer, I learned, was a man named Steve Duncan – a dashing, brilliant and possibly deranged individual who would become my first guide into the underground.

We met one afternoon on a trip to the Bronx, where Steve was plotting an excursion through an old sewer pipe. He’d begun exploring during his freshman year at Columbia University, where he would go slinking through a network of steam tunnels under the campus. Over the years, he styled himself as a guerrilla historian and photographer, with an alarmingly granular knowledge of the city’s infrastructure.

That day, we zigzagged between sewer grates, shining flashlights underground, tracing the route of the pipe.

My first solo descent was a gentle one: a walk through the West Side Tunnel – known to explorers and graffiti writers as the Freedom Tunnel – which runs for some two and a half miles beneath Riverside Park on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. On a summer’s morning, I slipped through a gap in a chain-link fence near 125th Street and headed through the tunnel’s entrance, which was voluminous, maybe 20ft high and twice that across. Every few hundred feet there was a rectangular ventilation grate in the ceiling, which, like a cathedral window, let in soft columns of light. I set off on a quiet walk through the middle of Manhattan without seeing another soul, like something from a dream.

The times I was above ground, I would trace and retrace the same path between work and home, following a narrow track of sensory experience. Down in the tunnel, however, I stepped outside those bounds, and connected to the city in a new and visceral way. I felt shaken awake, as if I was making contact with New York for the first time.

Going underground, crawling down into the body of the city, became my way of proving to myself that I belonged in New York, that I knew the city. I liked being able to tell my born-and-raised Manhattanite friends about old vaults beneath their neighbourhood that they knew nothing about. Down in sunken alleys, I enjoyed seeing textures of the city that were invisible to people on the surface: ancient graffiti tags, cracks in the foundations of skyscrapers, exotic moulds creeping over walls, decades-old newspapers crumpled in hidden crevices. New York and I shared secrets. I was sifting through hidden drawers, reading private letters.

Near the Brooklyn Navy Yard one night, Steve laid orange construction cones around a manhole and popped open the lid with an iron hook, releasing a twist of vapour from below. We climbed down the ladder, hand over hand on slimy rungs, and splashed down into a sewer collector. It was about 12ft high with greenish water burbling down the centre. The air was warm – my glasses immediately fogged. I hesitated before ducking under long, gooey strings of bacteria dangling from the ceiling – affectionately known as “snotsicles”. But the sewer was less repellent than I’d expected. The smell was not so much faecal as earthy, like an old farm shed full of fertiliser. We moved our lights over banks of loamy muck, like sandbars in a river, where tiny crops of albino mushrooms grew.

With each trip underground, the city cracked open a little more, disclosing another secret, just enough to draw me deeper. Each trip I climbed further down, taking risks that surprised even myself.

In the darkest strata I encountered the mole people, the homeless men and women who live in the city’s hidden nooks and vaults. One night, along with Steve and a few other urban explorers, I met a woman named Brooklyn, who’d been living underground for 30 years. She had a pocked face with dreadlocks piled high on her head. Her home, which she called her “igloo”, was an alcove hidden in the eaves of a tunnel. It was furnished with a mattress and a few crooked pieces of furniture she’d found. That particular day was Brooklyn’s birthday. We passed around a bottle of whiskey, as she sang a medley of Tina Turner and Michael Jackson songs, and for a while everyone laughed. But then something came undone, Brooklyn’s singing ceased and she became incoherent. She started seeing things that weren’t there. Her partner returned and the two of them fought, shrieking in the dark.

We have lived in caves and underground hollows for as long as humans have existed. And for just as long, these spaces have evoked in us visceral and perplexing emotions. The “dark zone” of a cave – the name scientists use for the parts of a cave beyond the “twilight zone”, which is within the reach of diffuse light – is nature’s haunted house, a repository of our deepest fears. It is home to snakes that twitch down from cave ceilings, spiders the size of chihuahuas and scorpions with barbed tails – creatures we are evolutionarily hardwired to fear, because they so often killed our ancestors. Up until about 15,000 years ago, caves all over the world were the dwelling place of bears, lions and sabre-toothed tigers. Even today, when we peer underground, we feel the flickering dread of predators in the dark.

As we evolved for life on the African savannah, where we hunted and foraged in daylight and where nocturnal predators stalked us in the night, darkness unnerved us. But the subterranean dark – “the sightless world” as Dante called it – is enough to cause our entire nervous system to splinter. The pioneering cave explorers of modern Europe imagined that a prolonged stay in subterranean darkness could permanently dismantle their psyches. One 17th-century writer described exploring a cave in Somerset: “We began to be afraid to visit it,” he wrote, “for although we entered it frolicsome and merry, yet we might return out of it sad and pensive and never more to be seen to laugh whilst we lived in the world.”

In some ways, this has turned out to be true. Neuroscientists have demonstrated manifold ways in which prolonged immersion in absolute darkness can trigger psychological aberrations. In the 1980s, on an expedition into the Sarawak Chamber, the largest known cave chamber in the world, in the Mulu National Park in Borneo, a caver entered one of the gigantic caverns. It was big enough to fit 17 football fields. He lost track of the rock wall and, as he drifted through the interminable darkness, the caver fell into a kind of paralytic shock. Eventually he was found and guided back to the surface by his partners. Cavers have referred to such darkness-fuelled panic attacks as “the rapture”.

The feeling of enclosure, too, leaves us unhinged. To be trapped in an underground chamber, our limbs restricted, cut off from light, with oxygen dwindling, may be the emperor of all nightmares. Down in any underground hollow we feel, if not a full tempest of panic, a reflexive tingle of not-quite-rightness, as we imagine ceilings and walls closing in on us. But ultimately, of course, it’s death we fear most. All of our aversions to the dark zone come together in the dread of our own mortality.

Yet, when we crouch at the edge of the underground, we do descend. Virtually every known accessible cave on the planet contains the footprints of our ancestors. Archaeologists have belly-crawled through muddy passageways in the caves of France, swum down long subterranean rivers in Belize, and trekked for miles inside the limestone caves of Kentucky, and everywhere they have found fossilised traces of ancient people.

And so, as I began to dissect my own preoccupation with the underground of New York, I found myself wrapped up in a much larger, older and more universal mystery. Despite the most basic evolutionary logic, we possess an impulse, buried in the core of our psyches, that draws us into the dark.

Over the years, I have travelled widely, yo-yoing between New York and remote corners of the world, following every thread in our tangled relationship to this subterranean landscape. From dank corridors beneath modern cities I went into older and wilder hollows, and finally into the ancient darkness of natural caves. To become conscious of the spaces beneath our feet is to feel the world unfold. We go down to see what is unseen, unseeable. Perhaps we go in search of the illumination that can only truly be found in the dark.

Underground: a Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt is published by Simon & Schuster at £16.99 on 24 January. Order a copy for £14.95 at guardianbookshop.com

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion