Going home can be disconcerting. Over the last few years, when-ever I have returned from New York, where I live, to Gloucester, where I grew up, what has struck me most – more than the rundown state of the local library, the decamping of the local newspaper to posher Cheltenham, the ailing, asthmatic feel of the town centre – are its ethnic transformations. Neighbourhoods that in the 1970s and 80s seemed like havens of timeless Englishness augmented by a few Asian convenience stores and smoky cafes vibrating to militant reggae are now full of Romanian grocers and Polish bakers. The shaven-headed guy trying to cadge a fag from me does so with a Spanish accent. A Commonwealth city has morphed into a European city.

In truth, my memory is playing tricks on me. For Gloucester, like so many cities across the country, has long been a hub for Europeans. My father used to work alongside Poles and Hungarians at an aeronautics factory and still laughs about the speed at which they ripped open their pay packets to buy Friday-night beer at the local pub. My sister’s best friend went out with a Ukrainian boy. The briefest memory-delve brings up stories of Italians and Maltese – and Scottish, many of whom had moved to this sleepy West Country city after the second world war. They were hidden in plain sight, their whiteness obscuring the centrifugality of their lives.

The intertwined histories of white and non-white immigrants in the postwar era have often been downplayed, if not flat-out ignored. One explanation is academic specialisation: it’s easier – and professionally advantageous – to focus on a particular demographic rather than to adopt a comparative approach. But it’s also the case that in recent times the life stories of those Britons with imperial roots, once regarded as untold or undernarrated, are now seen as more socially “relevant” than of those who hail from continental Europe.

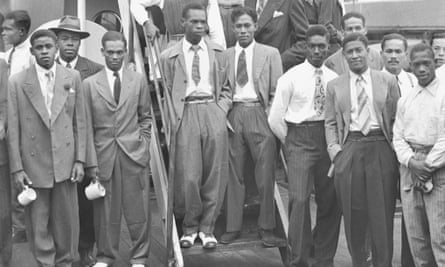

One of the many virtues of Clair Wills’s Lovers and Strangers is its unificatory zeal. She understands and documents the Windrush generation – Windrush being the name of the ship that brought nearly 500 West Indians to Tilbury in June 1948, as well as being shorthand for people from the British Commonwealth “coming home” to the mother country. But she is also interested in Latvians, Lithuanians, Cypriots and the largest immigrant group of them all: the Irish. By 1961, fully one-sixth of the population of the Republic was living in Britain.

Like today, the incomers were a motley mixture of migrants, refugees, former PoWs. Like today, many of them had been displaced by war, trekked across countries, had no homes to which they could return. Wills quotes Kathryn Hulme, who supervised one of the displaced persons camps in Germany’s American zone, describing the scramble to qualify for various recruiting schemes: “The bulletin boards listing all of the current avenues of escape made you think of some kind of macabre stock market that dealt in bodies instead of bonds.”

The popular press railed against “fascist Poles” and “enemy” Italians, while the Mirror targeted displaced persons: “They live on our rations – and live very well. They add to our discomfort and swell the crime wave. This cannot be tolerated. They must now be rounded up and sent back.” These sentiments were echoed by Vincent Brown, a banana boat stowaway from Jamaica, when he was caught fare-dodging in Bristol. “My life savings are diminished and I have parted with all my personal belongings. I came to England to find work. As British subjects we think we should be given preference for work in this country over Germans and Poles.”

Such resentment and enmity don’t tell the whole story; there was also conviviality and attraction. Wills describes an Irish missionary priest who was asked by a family to check on their emigrant daughter, who gossips claimed had been led astray. He describes what happened when he rang her doorbell: “Beside her stood a little mite of perhaps three years, with a ribbon in her hair. The girl admitted that she was married in the registry. ‘Is that little girl yours?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘What’s her name?’ ‘Fatima.’ ‘That’s a nice Catholic name.’ ‘Not at all; it’s the name of the Prophet’s daughter.’”

Wills is a distinguished historian of 20th‑century Ireland and she has a special talent for gleaning heartbreaking quotations, not least John Healy’s account of the emigrant train out of Mayo: “The Guard’s door slamming shut was the breaking point: like the first clatter of stones and sand on a coffin, it signalled the finality of the old life. The young girls clutched and clung and wept in a frenzy.” Or HL Morrow’s description of Irish workers on the mailboat to England: “Wretched-looking. The song knocked out of them. As they stumbled on board I noticed why: Each wore a label – like stock cattle. ‘British Factories,’ it said, simply. As if on their way to be spam-canned.”

Many women, from the Baltic to Barbados, headed to the UK in those decades after the war, but the stories that predominate in Lovers and Strangers are those of bachelor societies. It’s a tale of endless toil. Young Britons were increasingly reluctant to sweat it out in foundries and textile mills; Asian workers, who didn’t have to be housed, unlike labourers recruited in European camps, filled the void. They bribed foremen to get overtime shifts and squashed into dire accommodation in order to save money. Wills quotes from a Punjabi folk tune in which a woman sings of her exhausted partner: “My husband is an overtime man / No better than Woolworth’s goods”.

It is understandable then if Wills’s language veers towards the mordant. She characterises the immigrants of this period as living in “limbo” and, a touch overdramatically, claims they were “irrevocably cut off from the history that had made them”. At other times, though, she writes about the “avant-garde effect of immigration”; challenges the perception of inner-city mixed lodgings in the 1950s as “harbingers of disorder rather than crucibles of knowledge and experience about other people”, and portrays the new arrivals as frontiersmen representing a cultural vanguard.

Strangers and Lovers is brimming with new archival sources, careful cullings of governmental documents and oral histories – the book encompasses poetry and fiction as well as sociological accounts. It is at its most refreshing when it details the ways in which immigrants improvised and shapeshifted in their new environments: using forged documents to enter the country, being identified with the nation rather than the small town or village in which they had lived, adapting to the British diet by eating meat and drinking beer. There is even a story about South Asian workers who decide it’s too costly to visit prostitutes on their own and so hire one to come round to a terraced home once a week. The book ends in 1968, before the era when sectarianisms flourished and identities splintered.

All starting points are provisional. I wish Wills’s reinterpretation of the Windrush “moment” explored in greater depth the psychic realignments that took place during world war two. The historian Graham Smith, in When Jim Crow Met John Bull (1987), recounted an astonishing afternoon in August 1945 when hundreds of young English women flocked to an army barracks in Bristol where black GI soldiers were stationed. They protested about not being allowed to take leave of their departing lovers, sang Bing Crosby’s “Don’t Fence Me In” and broke through the barriers of the camp. Later they stood at the gates of the local train station and chanted: “To hell with the US army colour bars! We want our coloured sweethearts!”

Wills overemphasises how monocultural Britain was prior to the arrival of these migrants; its people had long been moving from country to city, north to south – to say nothing of across the empire. And it’s a shame the stories of white incomers such as the Latvians and the Maltese fade away from the narrative as early as they do here. Still, this is a generous and empathetic study that opens up the study of postwar migration in all its richness as well as inviting further investigation into the complex histories of British whiteness.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion