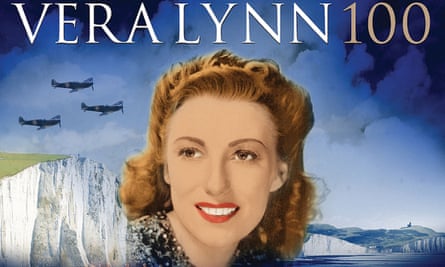

I climb the retractable ladder and hoist myself through the trapdoor into the loft. My eyes need time to adjust to the gloom and I move carefully, picking things up and setting them down gently, so as not to raise too much dust. A trunk lies open. What’s this inside? An old video of The Dam Busters; I bought it when the kids were small. And this? A tape of Vera Lynn: her greatest hits, with a picture of those white cliffs on the cover; we played it during long-distance trips in the car. I dig deeper. Here’s Winston Churchill as a toby jug, here’s a model Spitfire wrapped inside a copy of the Daily Express, here’s my souvenir coronation mug preserved like a sacred relic since 1953, and here’s my great grandfather’s medal from the second Afghan war.

These are the small, familiar things. But now I’ve got used to the murk, I can see the loft is bigger – much, much bigger – than I thought. That looks like a full-sized Trident missile standing on the mantelpiece, and the real House of Lords where the doll’s house used to be. This is such a big loft, in fact, that it can accommodate entire islands – the Falklands, Pitcairn, St Helena and the 11 other British Overseas Territories. There are people too. Some wear red robes with collars of fur. Another, a woman, has a crown. In a debating chamber, men jeer and wave paper at each other.

The cluttered attic is England. You might say Britain, but the essentials are English: the customs, the traditions, the pride in its very old parliament, the cult of the second world war, the anxiety to “punch above its weight”. “An unreformable old power” was how the Scottish writer and political theorist Tom Nairn described the United Kingdom in 2015, and that seems right. England, the head of the household, never wants to throw out the junk. The House of Commons lives by its old rituals; the House of Lords endures despite a century of tinkering; the winners continue to take all in Westminster’s first-past-the-post elections. Submarine-launched nuclear missiles and horse-drawn gold carriages help maintain the country’s self-esteem – the second to be used only on special occasions, and the first never at all.

Gordon Brown bravely suggested last week that this same kingdom, so shy of change, could only be kept together if it became a federal state. Federalism, he told an audience in his hometown, Kirkcaldy, would be a “Scottish patriotic way forward” to heal the bitter division between the Tory government in London and the SNP in Edinburgh.

If Scotland voted to remain part of the UK in the next referendum, then he wanted the powers that the EU would repatriate under Brexit to go to Edinburgh, not London. Scotland would take direct control of its fisheries, agriculture and industrial investment, and a greater share of taxation. The Scottish parliament would have the right to negotiate its own treaties with European and other countries on matters within its powers. Westminster’s responsibilities would run only to defence, foreign affairs that were outside Edinburgh’s scope and basic welfare provision.

How it would work constitutionally isn’t clear. Brown said that Wales and “the regions” should also have EU powers repatriated to them. A federal “trades council” would reconcile conflicts between the UK’s nations and regions. The UK parliament would continue to include Scottish MPs. By implication, there would be no English parliament and nothing that resembled a UK-wide assembly – converted, say, from the House of Lords – that would take those few decisions affecting the whole nation state.

It isn’t a federalism that other federal states would recognise, and the SNP of course dismissed it as stunt. But the bigger obstacle is England, which other than in the speeches of a few enthusiastic liberals has shown no interest in federalism for 100 years, and where the patriotic-sounding Campaign for an English Parliament still struggles to get noticed. In Nairn’s words from two years ago: “Most people in England, in my experience, are just not concerned enough. You know, ‘Things are fine as they are. What do we want to do all this for?’ In these conditions, confederation is permanently blocked. What option is there except nationalism round the periphery of the archipelago?”

And as it turned out, not just round the periphery: Scotland v London. What Brexit made evident was English nationalism: England v Brussels. One of the great attractions of the first is the prospect Scottish independence offers for renewal. In terms of the institutions and rituals of the state, its attic is nearly empty. Whatever the economic cost of separation, an independent Scotland can do as it pleases. It can decide (for instance) whether to be a monarchy, add a second chamber to its parliament, or abolish or adjust the honours system. England’s rejection of the EU, on the other hand, has come about partly because of the attic, which as the storehouse of tradition will now return to its position as the most sacred room in the house. Renewal isn’t the word.

As it happens, I like attics and the stuff they contain. In his new study of populism, The Road to Somewhere, David Goodhart attributes the Brexit and Trump revolts to a division in the population between the people he calls the Anywheres and the Somewheres. The Anywheres, typically, are liberally inclined graduates who attended a residential university, found a professional job, and never returned to the place they used to live. They amount to between a fifth and a quarter of the adult population. They are concentrated mainly in London and other big cities and university towns, and they value “autonomy and self-realisation before stability, community and tradition”.

By contrast, the Somewheres place a high value on security and familiarity, and have strong group attachments; the older among them pine for a lost Britain. Only a minority have attended university. They are less prosperous than the Anywheres and there are twice as many of them, living mostly in small towns, suburbia and the old industrial settlements, often only a few miles from where they were brought up. Not all of them voted leave – just enough.

Somewheres are attic people, but (as Goodhart concedes) many of us are a bit of both. I’m pleased to have my coronation mug, and I can still name the destroyers in the Royal Navy’s Daring class; but I left the place I grew up in when I was 18 and, other than on trips to see my parents, never returned. It’s strange now to consider how English nationalism occupies the role that Scottish nationalism used to have, when Britain represented modernity and Scotland meant Bannockburn: to take us up into the attic and back into the past.