Collateral Damage

- Author

- Prateek Rungta

- Published

With the release of iOS 9 and its support for content blocking APIs, there has been an explosion of ad blockers that are proving only too popular with users. This has kicked off the long overdue debate about the malpractices of contemporary online advertisers, and the ethics of blocking said advertising. There have been numerous interesting perspectives on this issue, and rather than recounting them here, I urge you to read them for yourself:

- What Happens Next Will Amaze You by Maciej Cegłowski

- Ad blocking by Seth Godin

- The ethics of modern web ad-blocking by Marco Arment

- Ad Blocking and the Future of the Web by Jeffery Zeldman

Instead, I wish to draw your attention to web fonts. A lot (if not most) of the ad blocker apps also support blocking of web fonts. Some restrict themselves to blocking font hosting services such as Typekit and Google Fonts, while others block all web fonts, self-hosted or otherwise. Designers, as some might have expected, have something to say about that.

The debate over content blockers is an important one for our industry. I just wish web fonts weren’t caught up in it.

— Jeffrey Veen (@veen)

September 18, 2015

As a designer “Block Webfonts” makes me… happy sad.

— iA Inc. (@iA)

September 18, 2015

@iA Webfonts (woff) actually are lean in data: 15 – 30kb/font. Stupid to block them because that decreases reading experience.

— Linotype (@Linotype_com)

September 18, 2015

So designers are not happy. But if you’re a user, chances are, you’re quite relieved (or even ecstatic) at the ability to block web fonts and experience a faster web. And web designers and front-end engineers have no one but themselves to blame for this.

How did we get here?

The web is primarily textual. Typography, thus, becomes an essential component of web design. CSS features such as @font-face allow us web designers to enhance the typographic quality of our designs by giving us the freedom to use any font at our disposal. This is a good thing. No two ways about that (and more of the same, please).

But somewhere along the way, we forgot (or chose to ignore) that a user’s experience of the web is made up of a wide range of factors, of which fonts are an important but not all encompassing part. Smooth performance and fast access to content are just as (if not more) important factors.

FOIT

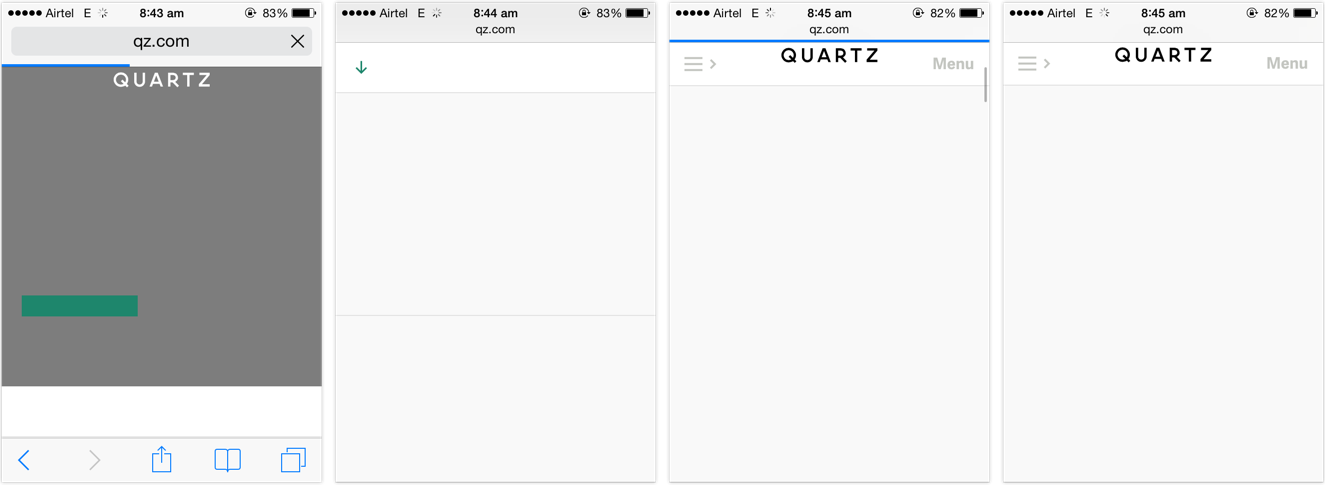

Far too many websites, far too often started resulting in situations such as this:

The page has been rendered. The content is available, but it isn’t accessible to be read until the web fonts finish downloading. This behaviour is called Flash of Invisible Text, or FOIT.

FOIT is bad if you’re on a low-speed connection, because the text might be the last thing that becomes accessible on the page. FOIT is worse if you experience bad latency or lose network connection altogether and the fonts fail to download, leaving you with blank spaces where the text might’ve been.

FOUT

There is an alternate method, which starts off with making the text available on first render using local fallback fonts from the user’s system and applying the web fonts after — and if — they finish downloading. This behaviour is called Flash of Unstyled Text, or FOUT.

Default browser handling of @font-face embeds has changed over the last few years, but web designers have more or less had control over going the FOIT or FOUT route right since web fonts gained popularity 1. Sadly, most websites chose invisible (FOIT) over accessible. They chose to hide the text until their preferred typefaces would finish downloading, resulting in longer wait times for the user. They treated web fonts not as an enhancement but as a requirement, seceding the functional high ground for higher quality typography.

Dear front-end developers, I’m on a train. I won’t mind a sudden switch of fonts, but I sure mind this endless wait for the fonts to load.

— Souvik Das Gupta (@souvikdg)

December 29, 2014

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that people want to be able to read the news report in Georgia or Roboto, or carry on with their shopping in Arial rather than stare at a blank screen for the rest of their train ride. Hence their joy and support for web font blockers.

The sense of dismay amongst designers hints at a deeper negligence. Why are designers disappointed on hearing that a certain feature might not be available to a certain subset of the people visiting their site? Is that not true for pretty much everything but the vanilla HTML we write? Or do we only concern ourselves for users with the latest software releases running on the most powerful hardware devices connected via the fastest networks?

With iOS 9 now able to block web fonts, it may be time for my amazing new paradigm-shifting dev methodology I call “Progressive Enhancement”

— Bruce Lawson (@brucel)

September 17, 2015

Web designers should know better. Websites should not come with minimum software requirements. Websites should not feel doomed if one, or two (or three, or more) of the enhancements are unavailable in a certain browser. Granted, typography is a vital component of web design given the percentage of text on our pages, but it should not come at the cost of the ability to read. The dependence on web fonts for delivering great reading experiences further highlights our mis-treatment of those web users that fall outside our local map.

Users are pushing back against the abusive practises of the online advertising industry. Some might feel that in between this fight, web font blocking is the unfortunate collateral damage, but I disagree. I feel the culprits are the websites that chose FOIT over progressive enhacement. In the process of users reclaiming faster access to content, even the FOUT style web fonts have been blocked. That is the real collateral damage.

Bram Stein has a great slide deck on the current state of web font loading and performance. Bram is also the author of the FontFaceObserver script, which is our weapon of choice to implement a progressive font loading strategy, based on the excellent work done by Filament Group. Recommended reading for web designers and front-end engineers. ↩︎