The number of measles cases has rebounded in Europe in 2017, after setting a record low in 2016. The continent recorded some 21,000 cases last year, according to the World Health Organization, which is nearly four times as many cases as in the year before that.

The surge in cases comes as a result of measles outbreaks recorded in 15 out of 53 countries in the region. The countries worst affected were Romania, Italy, and Ukraine, which each recorded about 5,000 cases. The WHO puts the cause down to a decline in routine immunization, low vaccination rates in marginalized groups, interruption in vaccine supplies, or lack of adequate disease surveillance.

“[This is] a tragedy we simply cannot accept,” says Zsuzsanna Jakab, WHO regional director for Europe.

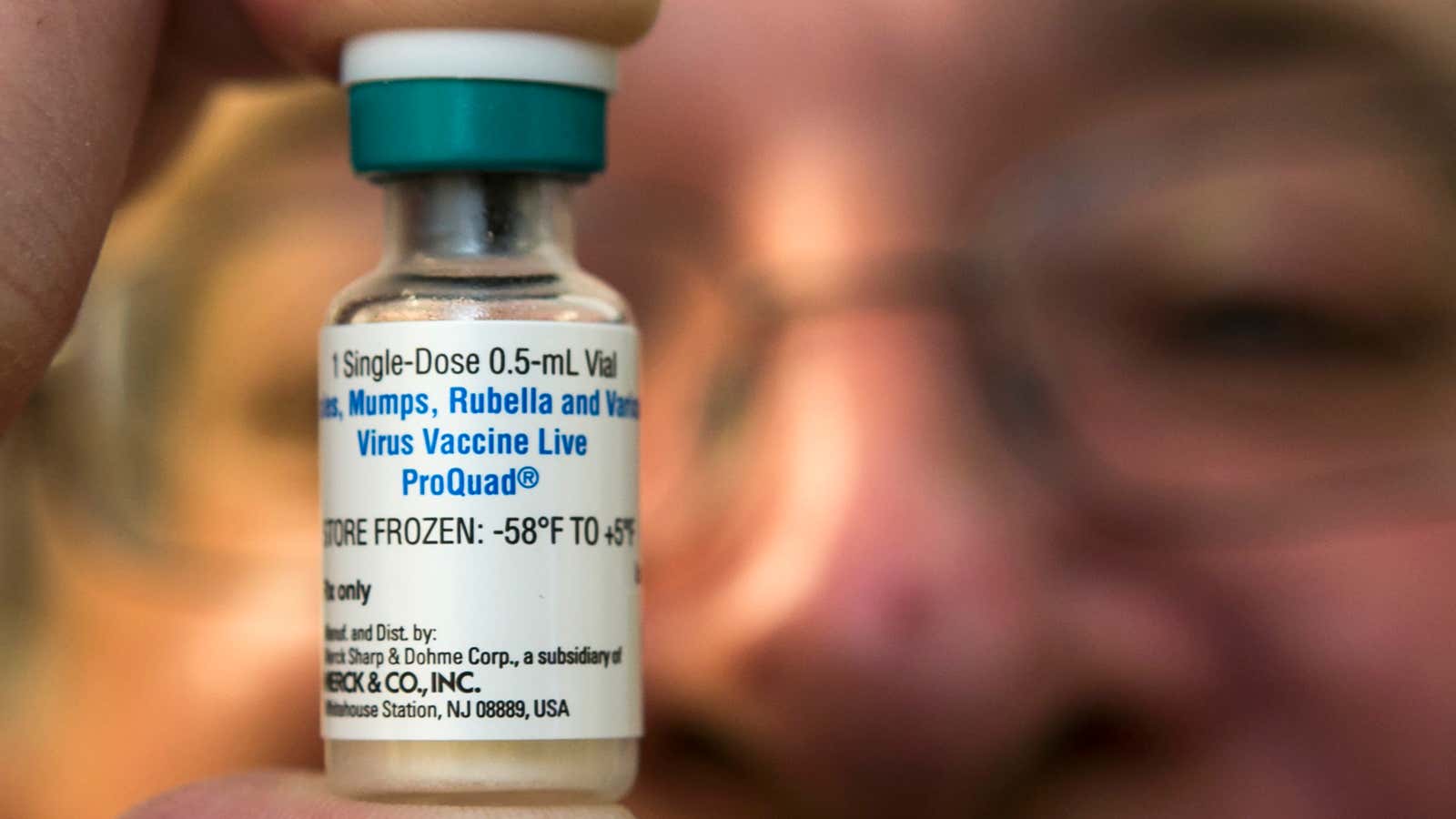

And Jakab’s right. As a group of mostly rich and highly educated countries, Europe can and should be able to tackle preventable diseases like measles. The solution to prevention is a single MMR vaccine that provides immunization against three deadly diseases: measles, mumps, and rubella.

In 2017, for instance, the WHO declared that the UK had eliminated measles. To be sure, “elimination” in this context doesn’t mean the UK didn’t have a single case, but that the number of cases was so low—only 282 cases—that the disease was confined to small groups and did not spread widely. To achieve the feat, UK’s national health service (NHS) recommends that the level of immunization in the population should be at least 90% to prevent the spread of measles and 95% to prevent the spread of mumps and rubella.

This level of immunization could eliminate the disease because of the concept of herd immunity. Here’s how Marcel Salathe, a professor of biology at Pennsylvania State University, explains it:

The basic idea is that a group (the “herd”) can avoid exposure to a disease by ensuring that enough people are immune so that no sustained chains of transmission can be established. This protects an entire population, especially those who are too young or too sick to be vaccinated.

Unlike the NHS, however, Salathe argues that in practice vaccination rates need to be much higher. That’s because the non-immunized population is not evenly spread out. So even though the average vaccination rate may be 95%, there may be some pockets where the rate may be lower than 80% and that’s low enough for the disease to spread.

Salathe says we should aim for 100% vaccine coverage to stop the spread of preventable diseases. In other words, if you’re thinking whether or not to get a vaccine, always lean towards getting it.