Everybody Should Be Very Afraid of the Disney Death Star

The first episode of the Streaming Wars is over. The rebels won. Now the empire strikes back.

Disney announced on Thursday that it would acquire most of the entertainment assets of 21st Century Fox for about $60 billion in stock and debt, in what would be the largest-ever merger of two showbiz companies. Already the most storied entertainment empire in the U.S., Disney would become a global colossus through this deal, gaining large stakes in the biggest entertainment companies in both Europe and India. The deal will almost certainly receive regulatory scrutiny, as the Justice Department has been lately dubious of mega media mergers.

The yuletide haul includes some of the most famous properties in television and film. In the transfer of power, Disney would receive the 20th Century Fox film studio, including the independent film maestros at Fox Searchlight (Best Picture Oscar–winners include: Slumdog Millionaire, 12 Years a Slave, and Birdman), the X-Men franchise, Fox’s television production company (worldwide hits include: The Simpsons, Modern Family, and Homeland), the FX and National Geographic cable channels, and regional sports networks, including the YES Network that broadcasts New York Yankees games. Disney also acquires a majority stake in the TV product Hulu, which it may use to kickstart its entry into the streaming wars.

These additions would enrich an overflowing treasury at Disney, whose assets includes Star Wars, Marvel, Pixar, ABC, ESPN, the world’s most popular amusement parks, and, of course, its classic animated-film division. When Mufasa tells Simba in The Lion King that “everything the light touches is our kingdom,” it isn’t just memorable screenwriting. It is corporate guidance.

The deal allows Rupert Murdoch, the billionaire patriarch behind 21st Century Fox, to consolidate his own kingdom—and his legacy—around the very place where he got his start: news. Murdoch, who built his $100 billion business starting with a single newspaper in Australia, would retain ownership of the Fox broadcast network, the Fox News Channel, and several national sports networks. Like an aging King Lear dividing the spoils in his twilight years, one of the world’s most famous media moguls is selling off his accumulated fortunes.

At the deepest level, this corporate marriage isn’t about Mickey versus Murdoch, or Avengers versus X-Men. It’s all about Netflix—and, to a subtler extent, Google and Facebook, whose dark shadows extend over the entire media landscape.

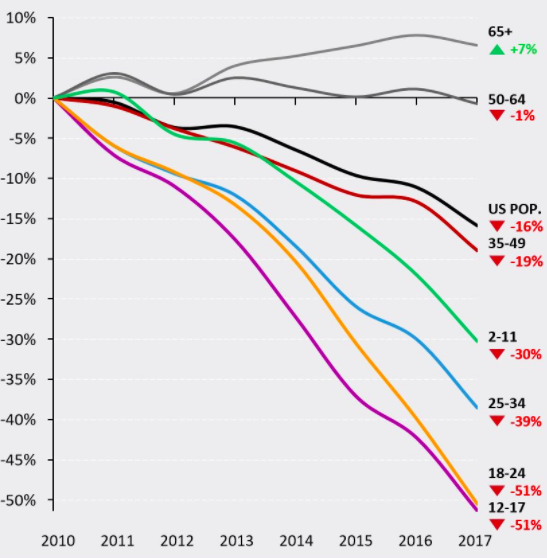

Streaming video has conquered pay TV and created a generation of cord-cutters; the youngest Millennials (those in their late teens and early 20s) watch 50 percent less traditional television (“cable TV,” as it’s commonly called) than people that age did in 2010. That means every content company now has to be a streaming technology company. As eyeballs shift away from the cable bundle, advertising is following them to mobile devices, where Google and Facebook have built an impregnable duopoly. That means every ad-supported television business has to become a direct-to-consumer business.

For media and entertainment companies, there is one big existential question: Get big and stream, or give up and sell? That is a choice that motivates both this deal and AT&T’s troubled bid for Time Warner. By making huge acquisition offers, AT&T and Disney have chosen Door No. 1. Disney’s future hinges on whether it can build a streaming powerhouse, or “Disneyflix”—a direct-to-consumer television product that, like Netflix, distributes a library of video over the internet to phones, tablets, and TVs. The company plans to launch an internet sports product in 2018 and—most importantly—a filmed entertainment product in 2019. To truly compete with Netflix, Disney’s 2019 service will need both a deep library for viewers ages 1 and higher (some viewers just want old shows and movies) and an excellent television production company (some viewers prefer new stuff). With this deal, it would have arguably the world’s best in both categories.

By agreeing to acquisition offers, Time Warner and 21st Century Fox have chosen Door No. 2. The latter group has seen a vision of their future—permanently falling live-TV ratings, more cinematic flops, quarterly job-cut announcements—and rather than wake up every morning in a hot sweat for the next 10 years, they’d prefer to sell high as fast as possible. Time Warner wants out of the movie business. 21st Century Fox wants out of the regional-sports-network business. It makes sense to sell to skittish behemoths that are both desperate and flush.

If one graph could possibly explain this entire deal, this one does. It shows change in traditional-television viewing time in the last eight years.

The upshot is pretty simple: Traditional television is a pure gerontocracy. The only age demo watching more TV than in 2010 are eligible for Medicare. By clutching Fox News (average viewer age: nearly 70) and other traditional TV channels, Murdoch is holding fast to the appropriately gray line. Disney is paying $60 billion to build a business that reaches everybody else—every youthful, colorful, nose-diving line segment in the chart. You could say Disney is spending $60 billion for a risky makeover to appeal to a younger demographic, while Murdoch is using the money to install a golden stair lift.

The Justice Department faces its own existential question: Namely, should this merger exist in the first place? The government has sued to block the AT&T deal on the basis that the combination of large distribution and content companies could be anticompetitive. But Disney’s long-term strategy is, like Netflix, to own the means of distributing its content. What’s more, this deal is a “horizontal” merger—i.e., between competitors in the same industry—which has historically attracted more negative attention from government regulators. If the Justice Department permits the Disney merger without a peep, it will feed speculation about why the government is blocking the acquisition of the president’s most-hated television channel.

With this deal, Disney would control as much as 40 percent of the the U.S. movie business (Disney and Fox films earned that share of U.S. box office revenue in 2016) and 40 percent of the U.S. television business (the new Disney would earn 44 percent of U.S. affiliate fees among major networks), according to data from MoffettNathanson, a media-research company. Its control of the sports-television landscape, between the regional sports networks and ESPN, might be even more concentrated, giving Disney’s more leverage to demand higher fees from cable and telco companies in exchange for distributing its content.

If that sounds a little scary for television distributors, or television viewers, then good. Everybody should fear the Disney Death Star. Hollywood studios should be afraid to compete with a corporate Goliath that could earn half of all domestic box-office revenue in a good year. Every tech company should be afraid to get into a content war with a company that combines the top blockbuster movie studio, with a top prestige-film company, with a world-class television production company, with the most valuable franchises—Star Wars, Marvel, Pixar, and X-Men—in the world. And consumers should fear too; not just those who are afraid that Disney will water down artsy filmmaking (like Fox Searchlight’s Grand Budapest Hotel) and R-rated superhero films (like X-Men’s Deadpool), but also those who are afraid that too much control of any industry confers monopoly power that restricts choices, raises prices, and hurts workers.

But here’s the truly weird part: Disney should also be afraid of its own Death Star. (After all, the thing keeps getting blown up.) In the last fiscal year ending in October, Disney’s made $55 billion in revenue, with about 60 percent coming from television and film (the rest came from parks, resorts, and merchandise). That 60 percent is endangered: Box-office ticket sales have been flat or declining for years, and television is in obvious structural decline. In many ways, the entire company’s future hinges on its ability to funnel its expansive universe of entertainment into a single direct-to-consumer stream that takes on Netflix, which already has more than 100 million subscribers worldwide. These sort of corporate transformations are treacherous, even when they are necessary.

The future of media is going to a very long, very expensive great-powers war. There’s no question that, as of 2017, the streaming rebels are winning. With this deal, the empire just struck back.