“Where are you?” Abdul asked his wife over the phone.

“I don’t know.”

“Are you in jail?”

“Under examination, in a camp.”

“Is our son there?”

“Sorry?”

“Is our son available?”

“It’s so noisy here. I can’t understand, can you say that again?”

“Where is our son? Where is our son?”

This is the story of Abdul*, a 30-year-old Rohingya man who travelled by boat and arrived in Malaysia in February 2015.

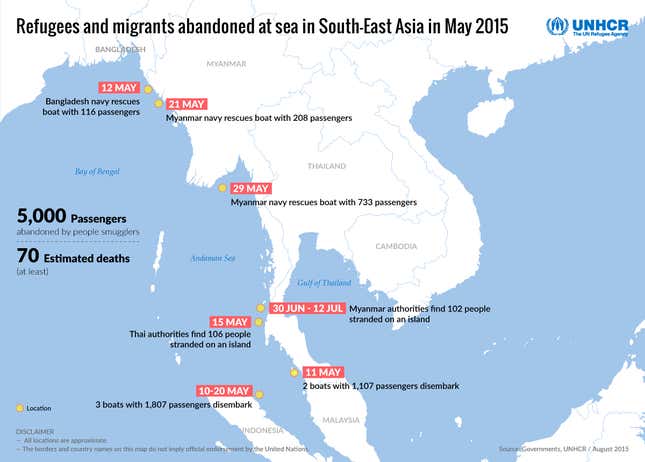

One month later, his wife and infant son set out from their hometown of Maungdaw in Rakhine State, Myanmar, to join him. They were among thousands of refugees and migrants from Myanmar and Bangladesh who soon found themselves stranded at sea that May, when the people smugglers and ship crews who had promised to take them to Malaysia abandoned them en masse in the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea.

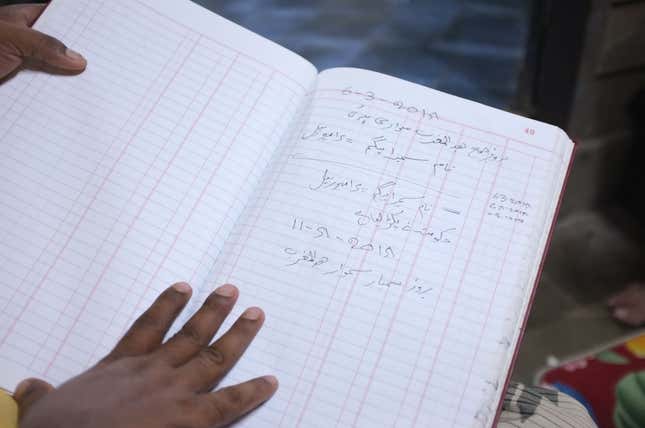

Abdul’s wife and son had boarded the boat on March 6. He knows the exact dates of all these events because he recorded them, as they happened, in a maroon ledger book. In the hundreds of interviews that the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has conducted with Rohingya like Abdul who have recently arrived in Malaysia, he is the first who kept notes about his journey, which took place at the end of 2014, before boats began being abandoned.

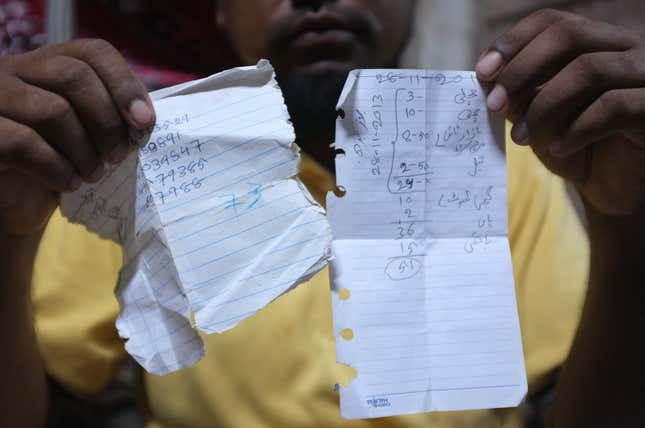

One of the crumpled notes Abdul unwraps from a wrinkled plastic bag has the number “73” written in blue. He had kept the number in his head while he was at sea, then wrote it down once he found some paper and a children’s crayon lying around the smuggler’s house where he was sequestered in February in Padang Besar, Thailand, on the border with Malaysia. It is the number of people Abdul says died on his boat.

Two of the 73 had sat within a whisper of Abdul, and he had shared betel nut with them, as well as worries and prayers. The first was a married man from Buthidaung who was visibly ill and struggled. The other was a single man from Maungdaw, who starved quietly until, one night, the person he was crouched next to could not wake him.

Most of the deaths were like this, Abdul says; there was just not enough food for the over 1,000 passengers he thinks were crammed on board.

After his own arrival in Malaysia, Abdul brokered a deal on April 11 with a Rohingya agent aboard his wife’s boat. The agent acted as a kind of switchboard operator for smugglers demanding payment from relatives, and would allow Abdul to speak to his wife regularly so long as Abdul topped up the agent’s Malaysian SIM card.

Soon after, Abdul’s wife told him from that their son was sick. He became desperate to get them off the boat, so despite warnings not to, he called one of the smugglers, unsolicited. Abdul has a recording of the call, which begins with Abdul introducing himself as a mullah. The smuggler, apparently driving somewhere in southern Thailand and curiously safety-conscious, says he needs to pull over to talk.

“My wife is with our baby, and the baby is sick,” Abdul tells the smuggler. “I would like to request you to kindly bring them to shore.”

“Mothers with small children,” says the smuggler. “There are 22 mothers and 22 small children.” He explains that the women and children have been particularly difficult to disembark, because they are less able to walk through the night undetected. “Can we stop the children from talking?” the smuggler asks, rhetorically.

“Brother,” says Abdul. “My child isn’t big enough to talk. He isn’t even one.”

In both this and another call, Abdul and the smuggler develop a peculiar, strategic rapport. Abdul repeatedly begs the smuggler’s forgiveness for disturbing him, while also reiterating his status as a mullah. And the smuggler seems to heed this subtle warning, expounding on what God would want him to do, boasting of how many Rohingya he has helped reach and survive in Malaysia. “By God’s blessing, I did it,” the smuggler says. “That doesn’t mean I am praising myself.”

Near the end of one of the calls, Abdul directly makes an offer to pay for his wife and son’s release.

“I am a mullah. I am saying this for you to consider. Is the market price right now 7,000 ringgit ($1,650) per person?”

“Okay, I understand,” the smuggler says. “Please be patient. Don’t pray against me. Please don’t do that.”

“No, not today. Even until the judgment day, I won’t pray against you, because you are the only one who is helping people.”

“Let me see what I can do for you, and where God guides me. Pray for me now, I’m driving, and a military man is waiting for me.”

“Assalamualaikum. If there’s an emergency, if I call you, please pick up.”

“I have to deal with 1,400 people. Don’t call me. I’ll call you back.”

When UNHCR first met Abdul on May 3, he knew his wife and son were at sea, but he did not know where. A few days later, around May 7 or 8, his wife told him the entire crew had abandoned ship in a speedboat and directed the passengers towards Malaysia.

The Thai number Abdul called to reach his wife worked for two more days after her boat was abandoned, then cut out, Abdul believes, because his wife’s boat had moved into Malaysian territory near the resort island of Langkawi.

The boat was one of two that arrived in Langkawi on May 11, carrying a total of 1,107 passengers. All transferred to the Belantik Immigration Detention Centre in Kedah.

Through a contact in Alor Setar, Abdul was able to speak to his wife again on 21 June. When he met with UNHCR the next day, he played a recording of the call that was saved on his phone along with a photo of his wife and son outside their home in Maungdaw.

On the call, Abdul’s wife tells him that their son is still sick, but when Abdul tries to understand what exactly ails his son, the contact from Alor Setar jumps on the line.

“I’ll call you back later,” the contact says. “Don’t worry.”

“Can you hand the phone to my wife, please.”

“They won’t allow it,” the contact says, referring to the authorities. “Because she’s crying.”

“She won’t cry. I’ll tell her not to cry. Just give her the phone for a while.”

“Hello,” says Abdul’s wife. “Be careful.”

The contact interrupts again. “I don’t know why she’s saying, ‘Be careful.’ There’s nothing to worry about.”

Abdul has not spoken to his wife since then. The contact has not called back, and his number is no longer in service.

*Abdul’s name has been changed. At least 5,000 passengers on the boats abandoned in May eventually disembarked in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand. Since 2014, nearly 100,000 people are believed to have embarked on the same journey as Abdul’s wife. An estimated 1,100 have died at sea due to starvation, dehydration, disease, and beatings by smugglers and crew members.

UNHCR has since been granted access to Belantik Immigration Detention Centre, but is still in the process of identifying all the Rohingya individuals detained there. More stories of survivors from the boats that landed in Indonesia are available on the UNHCR website.