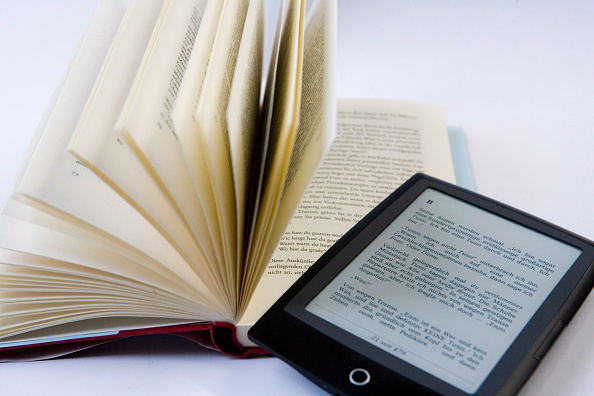

Are print books really making a comeback? Or are publishers doing a good job of making print more attractive by increasing the prices of the same books in digital format?

A recent story in The New York Times, “The Plot Twist: E-Book Sales Slip, and Print Is Far From Dead,” makes it look like the e-book trend is trailing off. It reports:

But the digital apocalypse never arrived, or at least not on schedule. While analysts once predicted that e-books would overtake print by 2015, digital sales have instead slowed sharply.

In the sixth paragraph, though, the story reveals that its main source for this information is a report from the Association of American Publishers, which includes data from almost 1,200 publishers, according to a spokesperson for the organization. In other words, it is a picture of the sector of the e-book market that’s flagged ever since it reluctantly entered it: mainstream publishers.

The Observer checked in with Smashwords, an entirely electronic bookstore, to corroborate the Times‘ numbers. The experience there somewhat squared. Mark Coker, the company’s founder, wrote the Observer via email: “The overall trend is flat to weak the last couple years.” He expounded more on this on the company’s blog in November.

Most e-books are sold on Amazon (AMZN), however. As Author Earnings recently reported, AAP members sell only 32 percent of the total units of e-books sold on Amazon and have dropped to 50 percent of total revenue in the largest e-book market. Author Earnings is able to get a very large sample of a broad cross section of e-book sales on Amazon, across the market, each month.

With that in mind, the Times story adds:

E-books’ declining popularity may signal that publishing, while not immune to technological upheaval, will weather the tidal wave of digital technology better than other forms of media, like music and television.

As the Observer previously reported—more people are earning more money as writers now than ever before. In other words, publishing isn’t just doing all right in the digital world, it’s thriving.

In fact, e-books from indie authors are no longer a trivial portion of the market. Author Earnings estimates that indie authors command a 42 percent share.

The most compelling data point from the Times story is the return of bookstores, writing, “The American Booksellers Association counted 1,712 member stores in 2,227 locations in 2015, up from 1,410 in 1,660 locations five years ago.”

It’s a telling point. As the Observer argued in a recent story on how lower e-book prices increase revenue, existing publishers have their strongest relational ties with bookstores. So, as they steadily lose ground, no matter how hard they try, in digital sales, it’s no surprise that AAP members are doubling down where indie e-book authors can’t compete: in bookstores.

It’s not till seven paragraphs from the bottom of a long story that the Times hits the critical point, writing:

As publishers renegotiated new terms with Amazon in the past year and demanded the ability to set their own e-book prices, many have started charging more. With little difference in price between a $13 e-book and a paperback, some consumers may be opting for the print version.

In other words: could it be that increasing prices from 20 to 30 percent decreased the popularity of those e-books?

It’s really stunning that the dramatic price hike from the leading AAP publishers goes unmentioned in a story about declining sales until so late in the story. Somehow, in fact, publishers managed to take the fact that they are losing market share and somehow turned that into a sunny business success story (a point Fortune has also made).

Digital books have certain drawbacks over print, such as the fact that print has a secondary market and digital doesn’t (for now, though the block chain could fix this). However, with an effective marginal cost of zero, every reasonable person agrees that e-books should cost less.

And that’s why indie writers are making more money in the field than major publishers, because not only are they offering more books that hit more specific tastes, but Internet-savvy writers also charge far less. For both reasons, they continue to gain ground.