It was on the eve of the 45th anniversary of his historic mission that Astronaut and sixth man to walk on the Moon, Edgar Mitchell, passed away at a hospice in Lake Worth, Florida. A fitting conclusion for a man who is leaving behind a legacy and philosophy to world, in addition to having a profound, and direct personal impact on my life.

In the first days of what would become my space beat for the Observer, I traveled to the home of the retired Astronaut to speak to him about his tumultuous, bold life in aerospace and aviation. Mitchell’s perspective on his journey to the Moon would reset my interest and reawaken the wonder that I experienced as a space-pondering adolescent growing up in New York City.

As a young first-generation American, I often thought the possibilities of what I could achieve in my life were limitless. Like many young men and women, I dreamed endlessly of traveling the stars. But those lofty ambitions fade as we grow older everyday and as the world around us comes into focus. I was no exception.

My imagination as a child was always stirred by what was right above me. Our home was just a few miles away from JFK Airport and larger-than-life airplanes would routinely fly overhead. From my perspective, they felt close enough to touch and this drove my curiosity. “How is this possible?” I thought. The idea that humans could fly became an obsession. I remember the day in the 4th grade when I learned about Neil Armstrong taking those first steps on the Moon as well as the brave men of the Apollo program that followed him. I was baffled and excited.

These experiences came rushing back to me last April on the long drive to Lake Worth, on my way to visit one of these explorers. While my childhood wonder returned briefly, it was accompanied by guilt and shame. I had become jaded towards the aerospace industry and had let my early interests in man’s journey into space atrophy.

After graduating Public School 108 in Queens, I attended Virgil I. Grissom Junior High School that was just a few miles from my home. I was lucky enough to have a math teacher that taught us about our school’s namesake despite its tragic history. “Gus” Grissom was an Astronaut in NASA’s Mercury program and the second American to go to space. Along with Ed White and Roger Chaffee, Grissom was killed during an Apollo 1 pre-flight test at NASA’s in Florida.

This disturbed me. NASA had always been, in my eyes, filled with adventurers and heroes who were beyond flaws. My teacher, Ms. Accardi, knew that we were too young for the reality of what happened to Grissom so she tried her best to inspire hope. Around that time, the International Space Station was in its first year of operation and we learned everything we could about it in our Math class. Ms. Accardi had even coordinated a live viewing of Senator John Glenn’s return to space as the oldest Astronaut to do so.

The project for that year was to build a replica of the ISS going on the information that was available through NASA. While I can’t recall how we pulled this off in the early days of the Internet, I do remember us completing a neat replica and the school’s administration putting it on display. It was even visited by then first-lady Hillary Clinton who was anointed Principal for a day of our Junior High School. The magnitude of this experience escaped me at the time but became more clear when the first lady invited myself along with other students to the White House.

Later that year, Ms. Accardi found a new and competitive project for her best students to explore the nature of space exploration. She had organized a day at the Buehler-Challenger & Science Center in New Jersey for us to partake in a mission simulation. Early in the project I was a shoe-in for participation but that faded over a few months. The violence I experienced inside and outside my home had made me despondent and careless. I stopped doing homework and began to skip classes.

Seeing the problem evolve, Ms. Accardi pulled me out of class and told me my spot on the field trip was in jeopardy. I broke down in tears and promised to do better. She went above and beyond to help me catch up with the course work and I made the cut. My assignment at the Buehler-Challenger center was to build a probe and the experience rekindled my academic pursuits.

8th grade was far more different. The city’s public schools had reached a tipping point in overcrowding and exhaustion of their budget. Large swaths of our schoolyard became occupied with trailers to hold the extra students while gang violence and drugs began to plague our school. I knew then that I had to attend high school very far from the neighborhood if I wanted to stand a chance in the world. I decided to enroll at Aviation High School in Long Island City. A three-hour round trip from my home.

My first year there was the most successful academic year of my life. I had straight A’s in the basics and even excelled in my aviation courses which added almost three hours to what New York City high school students are used to in a day. While I would have graduated with airframe and power plant licenses along with my diploma, I had every intention of attending an Ivy league school to pursue either science and engineering with the dream of one day working at NASA.

The summer after my freshmen year, my family suffered a tragedy that washed away whatever innocent outlook on life I had left. The sight of airplanes flying above my home was replaced by an inferno. My home was set ablaze by an electrical malfunction in the attic that burned the entire top floor. While my family lived on the ground floor, most of our belonging were damaged by the

My family had now lived in the single-room basement while we waited for our house to be rebuilt. A few days before my sophomore year we moved back in and I was eager to put everything behind me.

Just a week later, an event unfolded through the windows of my math class window would completely change my view of the world further discourage my ambitions. As the focus of the class shifted from the blackboard to a fiery hole in of the towers of the World Trade Center, we watched an airplane fly into the other. Chaos and horror ensued as we witnessed the very innovation we were studying be used to commit one of the worst atrocities in modern history.

The aftermath of the attacks had settled a little over a year later and I continued with my career pursuit until another fateful morning that would have lasting effects for our country. I had woke up early to watch the re-entry of the Space Shuttle Columbia just to see it disintegrate leading to the deaths of the entire crew and essentially the end of the beloved shuttle program.

This was the straw that broke the camel’s back for me. All interest in my career pursuits had vanished and I was now without aim or goals. It was just a few months later that I stopped showing up to school altogether. It wouldn’t be until a decade later when I re-entered the world I once dreamed of working in. After years on the fringes of society, through failed attempts at other academic pursuits, dead end jobs and life-crippling demons, I found myself at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center as a social media correspondent—a program I had applied to on the recommendation of a friend and with zero expectations.

I was a fish out of

I didn’t fully comprehend what I experienced and even my family and girlfriend at the time noticed a dramatic change in my personality. I needed some clarity and that’s when I pursued a meeting with an individual who had famously experienced a dramatic shift in perception—Astronaut Edgar Mitchell.

While he was one of the few men to walk on the Moon, his post-NASA career has been mired in controversy due to his outspoken views on the existence of extraterrestrials. While his beliefs are something that I share, I didn’t know what to expect from the aging scientist. Mitchell was welcoming and very enthusiastic about his career as an explorer. He spoke with confidence and clarity as he discussed his role in the Apollo 14 mission and even recalled specifics despite the long passage of time.

We sat down in his living room surrounded by books that included topics from Quantum physics to Botany. His dogs wrestled playfully around us, we discussed his experience of going to the Moon. “Well it was an incredible feeling and certainly life-changing,” he told me.

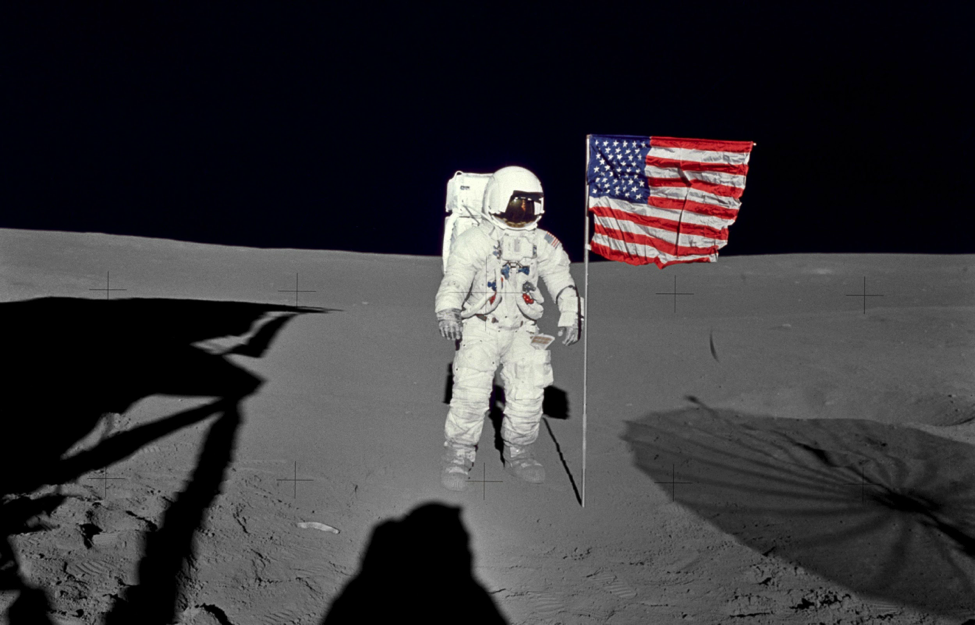

Edgar Mitchell is often cited in discussions of the “Overview effect” where an astronaut experiences something only a few humans have the privilege of—seeing Earth from the space.

Mitchell described it to me as, “Simply appreciation for our role and significance in the universe.“

“Seeing it in that perspective was quite the experience and seeing the Earth as part of the heavens changes your own personal perspective. My role in the universe completely shifted. I saw myself as part of a bigger cosmic picture.”

This is what I was looking for and exactly what I needed to hear. That the distractions and conflicts I had internalized were inconsequential to what I could achieve and we could achieve as a civilization. A simple realization that we are not shackled to the demons and failures that—if we let them—define who we are. For me, re-entering the world of exploration and discovery began with accepting that no matter has happened, I was part of a bigger, ever-evolving picture and I wanted to return to pursuing an active role in it.

“Being part of a larger reality for me was a life changing experience,” said Mitchell. “I had to do that to find out what are we going to do to making it better.”

Meeting Edgar Mitchell was a turning point in my life and brought the last two decades into focus. I have to believe that no matter what we’ve been through as a civilization, there are better days in front of us. Men like Mitchell have proven without a doubt that we can push the boundaries of exploration and technological innovation despite the many obstacles.

It’s no secret that NASA has faced hard times over the past few years since the closure of the shuttle program but as I’ve witnessed first-hand, the agency is fully committed to and engaged in sending the next class of human explorers to Mars.

Today, I get to tell that story for a living. It wouldn’t be possible without the great man we just lost.

I miss him already.