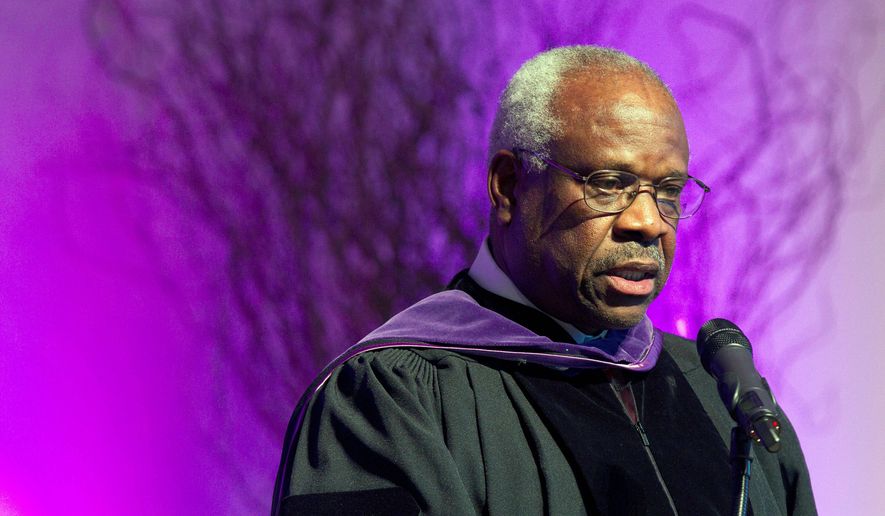

Of the 112 justices appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court since its inception, only two have been black — and the second one apparently isn’t worth consideration, as far as the new National Museum of African American History and Culture is concerned.

The Smithsonian museum still has “no plans” to include in its exhibitions a reference to Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, one of the high court’s conservative stalwarts who celebrates his 25th anniversary on the bench this year.

From his dirt-poor beginnings in Pin Point, Georgia, where the family home had no indoor plumbing, to his Catholic school education, Yale law degree and federal judgeship, Justice Thomas’ life embodies history as it spans the Jim Crow era, the civil rights movement, affirmative action and “post-racial” modern times signaled by the election of President Obama.

But liberal critics have long dismissed the black conservative jurist’s achievements, questioned his “authencity” and denied his influence on the court.

John Eastman, founding director of the Claremont Institute’s Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence, says Justice Thomas’ exclusion from the African-American museum is part of a broader effort to disappear black conservatives who deign to think for themselves.

“The persistent efforts to undermine Justice Thomas and his compelling body of jurisprudence, and to ignore the spectacular Horatio Alger story of his life, are part of a deliberate strategy to silence a conservative voice from someone who might serve as a transformative role model in the African-American community in particular, and the American community more broadly,” says Mr. Eastman, a former clerk for Justice Thomas. “Sad, really, that the taxpayer-financed institutions of our own government would join in such efforts.”

Congressional Republicans this week sought to rectify the situation.

Texas Sen. John Cornyn on Tuesday introduced a resolution asking the Smithsonian Institution to recognize the “historical importance” of Justice Thomas. A corresponding version was introduced in the House by Georgia Rep. Earl L. “Buddy” Carter and Texas Rep. Pete Sessions.

“I look forward to working with my colleagues in the Senate and the Smithsonian to hopefully correct this,” Mr. Cornyn said in a statement.

A Cornyn aide said the senator’s office has been in contact with the Smithsonian since the resolution was introduced.

Linda St. Thomas, chief spokeswoman for the Smithsonian, said the museum still has “no plans” to include a mention of Justice Thomas in any of its exhibitions.

“We do not have plans to create an exhibition on Justice Clarence Thomas or any Supreme Court justice as part of the museum’s inaugural exhibitions,” Ms. St. Thomas said. “The museum’s exhibitions are based on themes, not individuals.”

The 45-member Congressional Black Caucus — all Democrats — did not respond to several requests for comment.

The late Thurgood Marshall, the Supreme Court’s first black justice, figures in the museum for his role as an attorney in the Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, the landmark 1954 case that launched public school desegregation nationwide. Marshall’s membership card from a black fraternity is also on display, and the museum’s online database shows three black-and-white pictures of the jurist.

A search for Clarence Thomas, who succeeded Marshall on the high court, comes up empty.

‘An inspiring story’

The museum does mention one individual tangentially related to Justice Thomas — in the form of a pin-back button reading “I Believe Anita Hill.” Ms. Hill famously accused the jurist of sexual harassment in his 1991 Senate confirmation hearing.

“The confirmation hearing for Clarence Thomas is part of ‘A Changing America: 1968 and Beyond,’ because, as the label states, it ‘provoked serious debates on sexual harassment, race loyalty and gender roles,’” Ms. St. Thomas said.

Indeed, while the post-1968 exhibition couldn’t find space to spare for Justice Thomas, Anita Hill, the Black Panthers and the Black Lives Matter movement are well represented.

“This section illustrates the impact of African Americans on life in the United States — social, economic, political and cultural — from the death of Martin Luther King Jr. to the second election of President Barack Obama,” the description of the exhibition reads. “Subjects include the Black Arts Movement, hip-hop, the Black Panthers, the rise of the black middle class and, more recently, the #BlackLivesMatter movement.”

Ronald D. Rotunda, a professor of jurisprudence at Chapman University’s Dale E. Fowler School of Law, said Justice Thomas is widely regarded as one of the most influential jurists the Supreme Court has ever seen.

“I have no idea why the National Museum of African American History and Culture makes no mention of him,” Mr. Rotunda said. “Any objective telling of the history of blacks in American could not ignore him, even if you do not agree with him on anything.”

Carrie Severino, chief counsel and policy director at the Judicial Crisis Network, said the slight is appalling not only because Justice Thomas is one of the nation’s finest legal minds, but also because his personal story of overcoming poverty and oppression speaks to what is best in the American spirit.

“His story is really that of the American dream,” said Ms. Severino, a former Thomas law clerk. “Abandoned by his father at a young age, his mother wasn’t able to care for him. His grandfather was not a highly educated man, but by the force of his character, he was able to raise Justice Thomas and his brother with those kinds of values and character traits that made it possible for them to rise out of poverty.”

She said the justice’s story is one that museums are built to tell.

“It would have been enough for him to be a successful college graduate — that would have been historical, to be the first in his family,” she said. “But to be not just a graduate from Yale Law School, but to be sitting on the Supreme Court of the United States, it’s just hard to imagine the distance in his life that he traveled. It’s really an inspiring story.”

The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the 19th to be built on the National Mall.

The striking 397,000-square-foot structure — not one square inch of which is dedicated to Justice Thomas — houses more than 37,000 objects over 12 exhibitions, detailing the African-American experience from the fight to eradicate slavery to the struggle to secure civil rights.

The museum’s opening this September was attended by the two most recent presidents and their families. In a touching show of bipartisanship and national unity, former President George W. Bush and first lady Michelle Obama hugged on stage.

Ms. Severino said the glaring omission of Justice Thomas spoils what should have been a national celebration.

“I think it shows a significant blind spot for the organizers of the museum,” Ms. Severino said. “It’s an unfortunate one, because both his personal story and his incredibly significant role in our government was completely overlooked.”

• Bradford Richardson can be reached at brichardson@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.